During the civil war in Spain, the fascists and the Comintern sought to help the opposing sides in every possible way, sending both soldiers and military equipment. Special for our readers, we have translated a piece from the book "Tanks of the Interwar Period" by the Russian historian Yevgeny Belash, dedicated to the first battle of Soviet tanks in Spain. Using the Soviet commanders' reports, he shows not only the effectiveness of the Soviet tanks, but also investigates the reasons of the Republican defeat.

"…after that Gen. Walter picks a stick and goes on

the attack with a stick and his orderly.

The Scottish battalion rose and followed him."

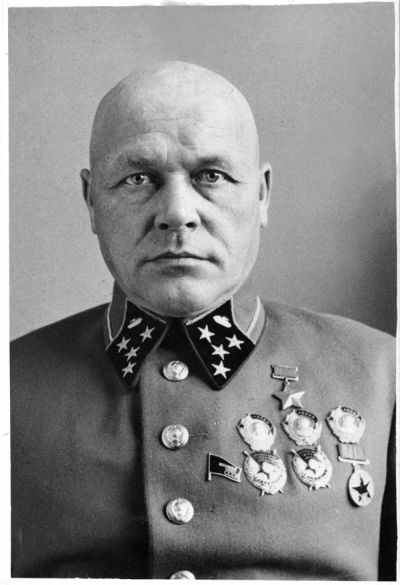

From the report of the Corps commander Pavlov, February 1938.

By the beginning of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, the country had only one regiment of Renault tanks, and in fact it was used more to create officer positions, being "a poorly capable shell, about two dozen tanks… From some works of fiction, one could conclude that the Spanish civilian population preferred more the spectacle of bullfighting than the spectacle of passing tanks".

The expansion of the Francoist revolt demanded, in the opinion of the USSR and the Republican government, urgent assistance. Moreover, they were ready to pay for it: as early as October 15, Spanish Prime Minister Largo Caballero and Finance Minister Juan Negrín officially approached the Soviet Union with a proposal to accept about 500 tons of gold for safekeeping. On October 20, Spain received the acceptance of the proposal and on October 22-25 the gold was loaded on board of the Soviet ships in Cartagena. A total of 510 tons of gold were taken on board.

How did Soviet tanks begin their journey to Spain?

According to major Armāns’ report, during the 6-day journey from Feodosia to Cartagena in October 1936 the Soviet tankmen worked through all the material they had on Spain: military-geographical and political-economic overviews. They also worked out several tactical and firing situations as applied to mountainous terrain. Armāns explained to each member of the group the task ahead during individual conversations.

On 13 October at 8 AM they arrived at the port of Cartagena. During the day the Soviet personnel cleared the deck of ZIS-5 trucks, unloaded some spare parts and fuel, and at night began unloading the tanks. The unloading lasted several days due to lack of knowledge of the language, disorganization of local workers and inadaptability of the port mechanisms to unload the tanks.

The unloaded tanks went by rail in two echelons of 25 vehicles each to the Archena base – the former resort. The rear in wheeled vehicles traveled along the highway on their own. The transfer took place during the day, given the respect already gained by Republican aviation from the enemy. Aircraft accompanied both columns in shifts, but their assistance was not needed. Groups of quartermasters on motorcycles prepared refueling and unloading points, positioned guards, etc.

The road was mountainous, with steep curves and sharp turns. The column was led by colonel Krivoshein in a passenger car, followed by a military technician with a repair team. Tanks’ speed reached 20 km/h, distance between them was 100-150 meters. Tanks were driven by Soviet drivers and commanders, with Spanish gunners in the turrets – the future tank crews.

Personnel of the training center were recruited mainly from communists, but also from socialists, there were even a few anarchists. The trainees were soldiers of the Republican Army who had been at the front and were qualified as drivers with 5 to 10 years of experience. The composition of the students was divided into companies – drivers, turret commanders, tank commanders, and motorists. There were 50 men in each company. The center was officially headed by former millionaire colonel Paredes, who had good organizational skills, especially in supply matters; Largo Caballero’s deputy was his friend. Each company commander was assigned a Soviet lieutenant advisor. The advisor had two commanders and three or four junior instructor commanders at his disposal. In addition the Soviet drivers and turret commanders were instructors for their respective courses.

Four tanks were provided for training. Spanish "showed great intelligence", quickly learning how to drive and fire from the ground; worse was the learning of materiel and the exact schedule of the day, because of the language barrier: "for them to start and finish classes in time was a straightforward accident”. Tactics, theory, and firearms classes for officers were taught by Krivoshein and Armāns in French language.

Tactical training of the Spanish officer was rated extremely low, "or rather, non-existent… The theory of firemanship in general was a novelty for them". About a thousand saboteurs and spies were "taken out" around the base in three months.

On October 17 they began regular training, expecting to continue until November, and on November 7 to begin the general assault in the Tajo Valley. However, on October 26 the tankmen were raised by order of the minister of defense and ordered to form a company of 15 tanks under Armāns command. In addition to the Spaniards-drivers and loaders, the other crew members were Soviet. All together there were about 200 men – 10 motorists, 20 commandant platoon soldiers, 40 Spanish drivers, 2 interpreters, etc., with 45 of them being "active".

During the night of October 26-27, the tank company unloaded at the Villacañas station and marched about 80 km to the town of Chinchon. On October 28, they conducted reconnaissance, establishing the position of the enemy and its units. By midnight the unit was concentrated north of Valldemoro.

On 29 October the Francoists intended to resume a decisive attack on Madrid, bypassing the fortified positions covering it from the west. Up to 2,000 infantry, up to 5 squadrons of cavalry, 3-5 artillery batteries and about 30 small Italian Ansaldo tanks (CV-35, which at that time in Spain, according to Italian data, were 15) were operating in the Seseña area. The Republicans also intended to make a private counterstrike from Valdemoro to Seseña, collecting on a front of 30 km 11,000 men, the main strike was supposed to be done by Lister's Brigade supported by 15 tanks. The tanks were to act as the infantry approached Seseña.

At 2 AM Lister claimed that one of his battalions and two battalions of Bueno's brigade were 2 km from Seseña, which would definitely be taken by morning. At 5 AM Armāns received a verbal order from Krivoshein that he should open fire on the infantry only after a thorough reconnaissance (because his own infantry could already be in Seseña). So Armāns sent out a combat reconnaissance of 3 tanks at 7 AM. At 7:30 AM they got a radio report from a combat outpost that Seseña was not occupied by the enemy, and at 7:45 AM they got a report with a motorcyclist from the vanguard battalion of Lister's Brigade:

"Seseña is not occupied by the enemy, give a white flare on your way to the western outskirts of Seseña, so you will not be hit by our artillery fire. Infantry coming into Seseña".

At 8 AM the main forces of the company, 12 tanks, approached Seseña in marching column with open hatches. Armāns, riding out from behind a hill, saw a gun directly on the road, pointing at the tanks, 100 meters away from the main tank. On the left of the chapel there were 200 men crowded near the gun and a crew of two officers with the rank of captain.

Armāns assumed it was their infantry preparing a circular defense, and to keep the gun from firing at him, raised his right hand clenched in a fist (the Republican salute) and shouted: "Salute!" Because of the clanking of the tracks he was not heard. When he came close to the cannon, Armāns demanded in French to remove the cannon and clear the way. He was answered in Spanish, then a lieutenant colonel officer approached. The following dialogue occurred, as Armāns describes it:

Lieutenant Colonel (in Spanish): Where are you going?

Armāns (in Spanish): Forward.

Lieutenant Colonel: Italiano?

Armāns: Yes (thinking that the lieutenant colonel was asking if I was looking for Italians).

Lieutenant Colonel: Fascisto?

Armāns: Yes, yes.

Lieutenant Colonel: Let's go to my headquarters and talk.

Armāns (in French): I have no time, I'm in a hurry.

At that time Armāns saw six Moroccans coming out of Seseña and realized that he was talking to the enemy – the uniforms and language of the sides were the same. Armāns ordered his tank commander Lisenko, who was sitting next to him on the turret: "Hostiles, third speed, stand still". Arman took into account that the tank, "standing on a slope, would easily take the third speed and immediately run over the lieutenant colonel standing at the left track and both captains together with the gun". Continuing to demand from the lieutenant colonel that the tank be let through sooner, Armāns heard the driver shift into gear and the tank was ready to dash. Giving the "move" signal with his foot, Armāns quickly descended into the tank "while the tank was moving over the lieutenant colonel and the gun". Slamming the top hatch, Armāns turned the turret toward headquarters and fired, signaling to the other tanks that the fight had begun – the first battle of the Soviet tanks and their crews in Spain.

Turned out that the Francoists were expecting Italian "Ansaldo" tanks that day, which helped Armāns. When the combat guard entered Seseña, the Francoists were really not there yet, only on the western outskirts the tankmen met the two incoming Moroccan squadrons and began to crush them without a shot being fired. The surviving horsemen scattered across the field without warning the main cavalry units or the Spanish Legion. About a battalion of Moroccans and a battalion of Legionnaires occupied the eastern edge along a ravine from the southwest, unaware of what had happened on the western edge half an hour before.

The fight began at 8:05 AM, when tanks, slamming their hatches, were destroying the dazed infantry, transports, cars, cavalry, and guns. On the northwestern outskirts of Seseña, the first tanks encountered two squadrons of Moroccan cavalry and almost completely crushed them. As they reached the western outskirts, the tanks turned their guns and shelled groups of infantry, artillery guns and machine guns that tried to turn against them. White flares were given from the commander's tank to alert his troops to the position of the tanks. Tank crew members climbed out of their vehicles and cut telephone wires despite machine-gun and rifle fire from 300-500 meters away.

Lieutenant Pavlov, whose tank's chassis was hit, got out of the tank under dagger machine gun fire, repaired the chassis, covered by other tanks, and then helped the seriously wounded turret commander – a Spaniard. Pavlov received several light wounds and a heavy concussion, but kept fighting.

The fight continued until 10:30 AM, when the 11th tank came out of Seseña. Armāns assumed that the 12th tank had not entered the village due to an engine malfunction. He later learned that Lieutenant Selitsky's tank, while following in the rear, had damaged its balancer and had pressed against the wall of a house in the middle of the village; the crew refused to move in with the others.

The tanks moved swiftly along the front line on the road to Esquivias, assuming the infantry were entering Seseña. In reality, the infantry, hearing the sound of unexpected combat, moved back 4-5 km and lay down without contact with the enemy.

The second battle began at 11:00 AM near the eastern edge of Esquivias. Tanks destroyed artillery, machine gun nests, and two Ansaldo tanks, one of which was dropped by Lieutenant Osadchy's ram into the gorge. On the Esquivias-Borox road the tanks were caught by aircraft, but the tankers misled the enemy by waving white handkerchiefs. There was no enemy in Borox.

After reaching the assembly area at 1 PM, Armāns collected the torn-off tanks until 3 PM, while trying to find out where the Republican infantry were. Four vehicles were missing – Klimov's, Lobach's, Selitsky's and Solovyov's. As a result, they decided to head north to connect with the infantry and rescue Selitsky's tank and search for the others.

North of Esquivias-Seseña the tanks in platoon columns got under fire by friendly artillery, so they turned east.

While passing through Seseña, a bottle of gasoline wrapped in a burning rag was thrown on Armāns' tank. The bottle broke and the burning gasoline poured inside, especially through the signal hatch, and the rubber gaskets caught fire. The tank commander received severe burns to his face and hands, while Armāns received less severe burns. The tanks coming behind hit the balcony with shrapnel shells and saw the blackened by fire tank of Selitsky with the killed crew.

The Solovyov's tank, which had crashed into a ditch, was found 500 meters from the eastern outskirts of the village. The crew of the tank fought off fierce Moroccan attacks for two hours. When help arrived some of the Moroccans managed to escape, about 200 of them were destroyed. After that all the fire of 11 tanks was concentrated on Seseña. Without the help of infantry, it was impossible to drive the enemy (tentatively a few dozen men and no more than 3 machine guns) out of the village and pull Selitsky's tank out.

Ju-52 then tried to bomb the tanks, but the pilots could not see the vehicles, which did not move so as not to give themselves away by moving their shadows. The infantry was found in Valdemoro, 9 km away from the tanks.

Results of the first battle: tankmen lost 3 tanks, 3 lieutenants and a driver killed and missing and 4 Spanish turret commanders. One captain, three lieutenants, one tank commander and four drivers were wounded, bruised, burned and contused, but all survived.

On the other hand, according to their words, 2 battalions and 2 squadrons were destroyed and scattered – about 800 men, 2 tanks were destroyed, 2 75-mm guns shot down and 10 75-mm guns were destroyed, 20-30 transports, 5-8 cars and 1-2 tank transporters were destroyed.

An attack on Madrid was thwarted.

The tanks showed "great power" and the ability to fight independently for 10 hours without infantry, the tank crew members showed "exceptional examples of heroism".

…

A total of 88 conventional and 4 commander's Pz.1 were sent to Spain. The Italians… delivered 129 light tanks. Whereas from the USSR to Spain came about 331-362 tanks T-26 and BT-5, 60-120 armored vehicles, not counting those produced in Spain.

Why did the Spanish Republic, possessing more numerous tanks, surpassing the enemy in firepower and armor protection, lose?

Bad crew morale? On the contrary, the reports constantly emphasize the courageous actions of both Soviet and Spanish tankers, reaching the point of bravado.

Weak reconnaissance, poor and often absent coordination of actions of Republican tanks with the infantry and other types of troops led to the fact that the tanks could not hold the captured territory or reverse the strategic situation. Thanks to the developed vehicles and infrastructure, tanks could quite successfully work as "fire brigades" in crisis sectors of the front, disrupting or slowing down the attacks of the Francoists at the tactical level, and could inflict certain losses on infantry or cavalry caught in an open place. But the tactics of anti-tank defense evolved faster than the tactics of tanks. Problems of interaction between the most diverse Spanish units, their commanders, Soviet specialists, and international brigades were also imposed. Whereas each subsequent blow of the Francoists, possessing a common initiative, brought them closer and closer to the goal. The better interaction between tanks, infantry, artillery and aviation ultimately allowed them to win even with not the most powerful tanks at that time…