The majority of the movements of ecology, like any approach is aimed at only one aspect of society (in this case, the preservation of the environment), are usually short-sighted.

So short-sighted that, although they often contribute to the common cause and can approximately recognize the causes of the problem, they do not have the answers so as to offer effective solutions.

However, do not be mistaken. Often, environmentalists altogether, instead of looking for reasons through scientific socioeconomic research, place all the blame on secondary issues, if not contrived, factors, such as lack of environmental education or demoralization and lack of cohesion of modern people. But this is all nothing more than the very tip of the iceberg.

We should seriously consider these topics for the good of humankind and therefore sweep these clowns from the scene, refute their stupidity, opposing all this with our indestructible scientific theory, popularize it, make it understandable for working people.

Some environmentalists openly reject and attack Marxism. They state that “Marxist thinking is a productive model that does not take into account the problem of the environment.” And sometimes they cite revisionist and frankly bourgeois regimes of the past and present as a graphic example (which shows how strongly the triumph of revisionism affected the worldview of the masses).

It is precisely these “one-sided movements” that attack Marxism, such as feminism, the animal rights movement, third worldism and other trends, which are far from the class struggle. Out of ignorance or deliberately, they lie, declaring that “Marxism does not delve into the problem of women”, that it “cannot provide a decent life for animals and care for them”, or that it “did not bother to find out the reasons for the backwardness of underdeveloped countries and find a solution for them”. These statements are incredibly ridiculous because it was Marxism that provided the scientific answer to the question of the causes of these problems and offered solutions for them.

In Marxism, there has always been an understanding that a person realizes themselves through labour, that in this way he socializes with his own kind and with nature. Therefore, for the founders of Marxism in the question of nature, it was impossible to ignore the human aspect. But, even knowing this, were they promoting a predatory model that opposed nature itself?

Critiquing capital and how it behaves, Marx states:

“Excess and intemperance come to be its true norm. Subjectively, this appears partly in the fact that the extension of products and needs becomes a contriving and ever-calculating subservience to inhuman, sophisticated, unnatural and imaginary appetites. Private property does not know how to change crude need into human need. Its idealism is fantasy, caprice and whim; ” <…>» (Karl Marx, «Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844》: Third Manuscript, «Human Requirements and Division of Labor Under the Rule of Private Property and Under Socialism. Division of Labor in Bourgeois Society».)

It is clear that under private ownership the environment becomes an object of immeasurable exploitation. In fact, under capitalism, man is faced with alienation from nature. The bourgeois is forced to prioritize the gain of wealth by any means, if necessary, even by harming nature, because otherwise, he risks being surpassed by competitors. Since all this is carried out at a high level of development of the productive forces, real natural disasters occur.

Likewise, the worker experiences alienation in his relationship with nature. He either does not realize how much harm his work brings to the environment, since the existence of the worker himself depends on this work, or his dissatisfaction with the situation does not lead anywhere, because neither how the product is produced nor how it is distributed, depends on him. Hence the need for joint organization with other people of his class – including on this issue.

How did Marx explain the capitalist economy and its direct connection with an employee with his environment?

«But while upsetting the naturally grown conditions for the maintenance of that circulation of matter, it imperiously calls for its restoration as a system, as a regulating law of social production, and under a form appropriate to the full development of the human race. In agriculture as in manufacture, the transformation of production under the sway of capital, means, at the same time, the martyrdom of the producer; the instrument of labour becomes the means of enslaving, exploiting, and impoverishing the labourer; the social combination and organisation of labour-processes is turned into an organised mode of crushing out the workman’s individual vitality, freedom, and independence. The dispersion of the rural labourers over larger areas breaks their power of resistance while concentration increases that of the town operatives. In modern agriculture, as in the urban industries, the increased productiveness and quantity of the labour set in motion are bought at the cost of laying waste and consuming by disease labour-power itself. Moreover, all progress in capitalistic agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the labourer, but of robbing the soil; all progress in increasing the fertility of the soil for a given time, is a progress towards ruining the lasting sources of that fertility. The more a country starts its development on the foundation of modern industry, like the United States, for example, the more rapid is this process of destruction.». (Karl Marx, «Capital», V. I. Part 4, Chapter 15, Section 10: Modern Industry and Agriculture).

Perhaps Marxism offers petty ownership (also known as “self-employment”) as a solution to such contradictions, or points to a different problem?

«Here, in small-scale agriculture, the price of land, a form and result of private land-ownership, appears as a barrier to production itself. In large-scale agriculture, and large estates operating on a capitalist basis, ownership likewise acts as a barrier, because it limits the tenant farmer in his productive investment of capital, which in the final analysis benefits not him, but the landlord. In both forms, exploitation and squandering of the vitality of the soil (apart from making exploitation dependent upon the accidental and unequal circumstances of individual producers rather than the attained level of social development) takes the place of conscious rational cultivation of the soil as eternal communal property, an inalienable condition for the existence and reproduction of a chain of successive generations of the human race. In the case of small property, this results from the lack of means and knowledge of applying the social labour productivity. In the case of large property, it results from the exploitation of such means for the most rapid enrichment of farmer and proprietor. In the case of both through dependence on the market-price.

All critique of small landed property resolves itself in the final analysis into a criticism of private ownership as a barrier and hindrance to agriculture. And similarly all counter-criticism of large landed property. In either case, of course, we leave aside all secondary political considerations. This barrier and hindrance, which are erected by all private landed property vis-à-vis agricultural production and the rational cultivation, maintenance and improvement of the soil itself, develop on both sides merely in different forms, and in wrangling over the specific forms of this evil its ultimate cause is forgotten.

Small landed property presupposes that the overwhelming majority of the population is rural, and that not social, but isolated labour predominates; and that, therefore, under such conditions wealth and development of reproduction, both of its material and spiritual prerequisites, are out of the question, and thereby also the prerequisites for rational cultivation. On the other hand, large landed property reduces the agricultural population to a constantly falling minimum, and confronts it with a constantly growing industrial population crowded together in large cities. It thereby creates conditions which cause an irreparable break in the coherence of social interchange prescribed by the natural laws of life. As a result, the vitality of the soil is squandered, and this prodigality is carried by commerce far beyond the borders of a particular state (Liebig).». (Karl Marx, «Capital», Part VI, Ch.47: V. Métayage And Peasant Proprietorship Of Land Parcels)

Marxism correctly points out that only with the end of private property and the creation of an economy of a social type will we put an end to both the problem of the production crisis and the antagonism that exists now between human and nature. Moreover, humanity and nature are doomed to mutual existence, because, as already mentioned, there is no social person without nature:

«Thus the social character is the general character of the whole movement: just as society itself produces man as man, so is society produced by him. Activity and enjoyment, both in their content and in their mode of existence, are social: social [This word is crossed out in the manuscript. – Ed.] activity and social enjoyment. The human aspect of nature exists only for social man; for only then does nature exist for him as a bond with man – as his existence for the other and the other’s existence for him – and as the life-element of human reality. Only then does nature exist as the foundation of his own human existence. Only here has what is to him his natural existence become his human existence, and nature become man for him. Thus society is the complete unity of man with nature – the true resurrection of nature – the consistent naturalism of man and the consistent humanism of nature.». (Karl Marx, «Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844》: Third Manuscript, «Private Property and Communism».)

It cannot be otherwise. Marxism explains: although capitalism satisfied the development of the productive forces, which was not satisfied with the feudal relations of production that impeded this development, at the present moment capitalism itself has exhausted its progressiveness for human history; because, like any exploitative regime, it generates its own contradictions.

This leads to the fact that productive relations eventually become obsolete and cannot control the development of the productive forces, which they themselves created:

«…In the development of productive forces there comes a stage when productive forces and means of intercourse are brought into being, which, under the existing relationships, only cause mischief, and are no longer productive but destructive forces (machinery and money);…» (Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, «German Ideology», 1846)

This leads to an anarchic economic model of cyclical crises:

«Modern bourgeois society, with its relations of production, of exchange and of property, a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells. For many a decade past the history of industry and commerce is but the history of the revolt of modern productive forces against modern conditions of production, against the property relations that are the conditions for the existence of the bourgeois and of its rule. It is enough to mention the commercial crises that by their periodical return put the existence of the entire bourgeois society on its trial, each time more threateningly. In these crises, a great part not only of the existing products, but also of the previously created productive forces, are periodically destroyed. In these crises, there breaks out an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity — the epidemic of over-production. Society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism; it appears as if a famine, a universal war of devastation, had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence; industry and commerce seem to be destroyed; and why? Because there is too much civilisation, too much means of subsistence, too much industry, too much commerce. The productive forces at the disposal of society no longer tend to further the development of the conditions of bourgeois property; on the contrary, they have become too powerful for these conditions, by which they are fettered, and so soon as they overcome these fetters, they bring disorder into the whole of bourgeois society, endanger the existence of bourgeois property. The conditions of bourgeois society are too narrow to comprise the wealth created by them. And how does the bourgeoisie get over these crises? On the one hand by enforced destruction of a mass of productive forces; on the other, by the conquest of new markets, and by the more thorough exploitation of the old ones..» (Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, «Manifesto of the communist party», 1848).

Did not Engels emphasize on the need to relieve the industrial centers and eliminate the differences between town and countryside?

«…Accordingly, abolition of the antithesis between town and country is not merely possible. It has become a direct necessity of industrial production itself, just as it has become a necessity of agricultural production and, besides, of public health. The present poisoning of the air, water and land can be put an end to only by the fusion of town and country; and only such fusion will change the situation of the masses now languishing in the towns, and enable their excrement to be used for the production of plants instead of for the production of disease.

Accordingly, abolition of the antithesis between town and country is not merely possible. It has become a direct necessity of industrial production itself, just as it has become a necessity of agricultural production and, besides, of public health. The present poisoning of the air, water and land can be put an end to only by the fusion of town and country; and only such fusion will change the situation of the masses now languishing in the towns, and enable their excrement to be used for the production of plants instead of for the production of disease.». (Friedrich Engels, «Anti-Duhring»)

This refutes all the chatter of those anti-Marxist environmentalists who reject Marxism on the pretext that it does not deal with environmental issues. Now, knowing this, we should talk about where to start looking for a new political, economic and cultural model that would harmoniously exist with nature.

Is it possible to implement a new environmentally sustainable model without ending the exploiting classes that dominate economics and politics, without destroying capitalism and the political structures that support it? No:

« …and connected with this a class is called forth, which has to bear all the burdens of society without enjoying its advantages, which, ousted from society, is forced into the most decided antagonism to all other classes; a class which forms the majority of all members of society, and from which emanates the consciousness of the necessity of a fundamental revolution, the communist consciousness, which may, of course, arise among the other classes too through the contemplation of the situation of this class.

(2) The conditions under which definite productive forces can be applied are the conditions of the rule of a definite class of society, whose social power, deriving from its property, has its practical-idealistic expression in each case in the form of the State; and, therefore, every revolutionary struggle is directed against a class, which till then has been in power.

(3) In all revolutions up till now the mode of activity always remained unscathed and it was only a question of a different distribution of this activity, a new distribution of labour to other persons, whilst the communist revolution is directed against the preceding mode of activity, does away with labour, and abolishes the rule of all classes with the classes themselves, because it is carried through by the class which no longer counts as a class in society, is not recognised as a class, and is in itself the expression of the dissolution of all classes, nationalities, etc. within present society;». (Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, «German Ideology»)

Is it possible for an ideological revolution that will lay the foundation for a new economic basis without destroying this political and economic power? Also no. In Marxism, the mode of production in a certain society is understood as that which affects the totality of dominant beliefs, values and ideas in the dominant culture:

«…Both for the production on a mass scale of this communist consciousness, and for the success of the cause itself, the alteration of men on a mass scale is, necessary, an alteration which can only take place in a practical movement, a revolution; this revolution is necessary, therefore, not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew.». (Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, «German Ideology»)

This is how Marx and Engels throw overboard the false arguments of both environmentalists and eco-socialists (about which we will have a discussion later). This must be borne in mind because currents of the late twentieth century, such as postmodernism, have made efforts to spread the myths about the attitude of Marxism to environmental issues. Postmodernists, having become environmentalists, but at the same time having remained open enemies of objectivity and materialism, were forced to lie about Marxism in order to get rid of a serious rival in the struggle for leadership in environmental matters.

«…we have discovered that nothing can be known with any certainty, since all pre-existing “foundations” of epistemology have been shown to be unreliable; that “history” is devoid of teleology and consequently no version of “progress” can plausibly be defended; and that a new social and political agenda has come into being with the increasing prominence of ecological concerns and perhaps of new social movements generally. ». (Anthony Giddens, The Consequences of Modernity, 1990[1])

Greta Thunberg, a 16-year-old Swedish schoolgirl who became famous for her high-profile campaigns to combat climate change became an icon of bourgeois eco-activism. She was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Environmentalists, whether from one trend or another, usually do not have a scientific worldview, and their own knowledge is one-sided and does not go beyond the fetish topic. As a result, they are unable to understand the fundamental causes of the problem they are talking about, in an idealistic form theorizing about what could have led to the problem, and offering even more idealistic solutions.

Therefore, many environmentalists – although they are distinguished by volunteerism and belligerence – when it comes down to it, tend to have excessive skepticism, subjectivism, relativism, romanticism and, as a result, “pose” more than really strive to find causes and solutions to the problem.

How is it possible to find a solution in environmental matters, not seeing that the roots of the problem lie in the development of capitalism? How will capitalism be overcome and the “sustainable model” they so often claim to be proposed, if they do not understand that capitalism is inherent in the disorder and waste of productive forces? How can an alternative economic model be proposed without jeopardizing the current model based on profit maximization in the free market? How is it possible to introduce mass environmental education outside of individualistic concepts, if awareness of environmental problems is imposed on capitalism since this is the economic basis on which the education and culture of a society are based?

These are the questions – even if they may seem untrue – that most environmentalists do not ask. And if they do, they come to the methods of half-measures tied to compromising with capitalism, its political, economic and cultural system, they are engaged in a reciprocal advancement of the idea that it is allegedly possible to create a kind of “green counterculture” within capitalism by peaceful means, without destroying either political nor economic power; it’s a doomed strategy from the hippie arsenal.

The results of this practice (if you can call it that) of “green reformism” are manifested in the role of “greens” in the European Parliament, which testify to how the EU countries in all treaties now divert from the topic of ecology.

Groups that call themselves environmentalists have as much chance of success in their struggle, as groups of feminists, anti-fascists, nationalists, anti-bullfighters [2] and other one-sided movements. All of them, not being equipped with the scientific methodology and analysis with which Marxism-Leninism is equipped, will remain only a fragment of a sad, if not shameful, “desire, but not the ability” to solve the problem with which they are so zealously “struggling”. They will remain forever prisoners of more and more bourgeois theories revolving around the topics they discuss.

Today it is very difficult to distinguish between bourgeois theories, only adapted by these groups, from theories that they create themselves, allegedly on their own initiative. The influence of the bourgeois superstructure leads to the fact that – even if they themselves deny it – most of their proposals, despite the protest orientation, are in reality acting as nothing more than patches. Such patches are offered by official politicians, whom environmentalists themselves often call to hate and call traitors to the cause of the environment.

It should be said that these groups play the same role as the yellow (company) unions: they shout and stamp their feet, but only until the first promise of adjustment within the limits, half narrower than required, and then call for calm and celebrate victory; sometime later, when the government does not fulfill the promise, they again trumpet the mobilization, and so on in a cycle.

This leads us to a conclusion that the presenters of ecology do not realize the greedy nature of capitalism at the stage of imperialism, they do not understand that capitalism cannot stop looking for ever greater profits and suddenly transform into a sustainable economic system that cares about the environment: in this case, it would no longer be capitalism.

Likewise, within the framework of capitalism, scientific research, the discovery of new technologies and renewable energy sources do not at all guarantee the path to the stability of the planet. Any patent belongs to a particular company, as is the case in the pharmaceutical or food industry. Capitalism makes a step towards renewable energy only due to the depletion of sources of non-renewable energy, in order to meet certain requirements of citizens and some international conventions, but always keeping in mind and prioritizing “maximizing profits”.

Only Marxism contains within itself a scientific doctrine capable of solving these problems such as national, gender, environmental or the problem of fascism. It will be nonsensical for a Marxist to trumpet that his party is “ecological” or “anti-fascist” because his doctrine covers all the contradictions generated by the capitalist production relations and answers them. The Marxist doctrine makes this much clearer and more serious than those who concentrate only on a particular topic.

As such, a Marxist is not concerned with saturating one’s messages with environmentalist slogans to “do the job.” One gives a materialistic explanation of the causes of the phenomenon and proposes real solutions, fights for their application and realizes that the main obstacle to their implementation is the exploiting and parasitic classes, which must be destroyed, otherwise the solutions will not be applicable.

Rare attempts by groups of “environmentalists” is to theorize anything in politics or economics and in turn create what has been called “eco-socialism”:

«Eco-socialism (also known as the Green Movement) is a political movement, born of the dust of May 68, which understands itself as a “leftist” and mixes the ideas of utopian socialism, romanticism, anarchism, social democracy, hippies, third worldism, alternative globalism and all similar ideological currents that have already been refuted by history itself. In some cases, ecosocialism developed on the shoulders of imperialist militarism.

We can consider that he is a part of the pro-imperialist “left”. The basis of their revision is the denial of the class struggle – the main axis of Marxism-Leninism and scientific socialism, the central element of social relations established by the mode of production, the desire of capitalism to own the means of production and to concentrate them; they replace the class struggle with the problem of environmental damage. They believe that the main contradiction of capitalism lies not within human society, but is associated with the environment, which is destroyed in the pursuit of maximum profits.

It is important to note that eco-socialists does not have a clear ideological structure due to the enormous influence exerted on them by other political currents, so that within eco-socialism itself, different approaches have appeared, and in some cases, they put social relations above relations with the environment, from which “red-green” or “watermelons”[3], but they do not go beyond proposals for cooperation within capitalism or the struggle exclusively against neoliberal politics.

Usually, they say that they are fighting capitalism, but at the same time they defend the institutions of bourgeois democracy, which is an expression of the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, they propose pacifist methods of activity (although there are circles close to anarchism among them, offering “resistance” – violent, but disorganized). In economics, they present debt relief as a solution for the modern neo-colonial world, not realizing that it is just another cog in a system born out of the very existence of property and usury.

They reflect on so-called “wealth redistribution” without bothering to see the root of these inequalities, believing that education can lead to an altruistic approach for companies to focus on renewable energy and propose for recyclable, reusable goods and public use technological patents. In a broad sense, eco-socialism is a petty-bourgeois concept, it is petty-bourgeois socialism». (Bitácora Marxista-Leninista, «Definitions», 2013[4]).

An example of this is the Popular Unity Candidacy [5] in Spain. In words, it offers a kind of “ecological economy” (sic), while in terms of the form of ownership, it is a “mixed economy”. Within this new economy, the open existence of the private sector is recognized and, on the other hand, it is assumed that the state and the cooperative sector will be tied to capitalist laws such as the “law of value”, “the law of supply and demand.”

Thus, these revisionists believe they can solve the problem with one stroke of the pen, in one idealistic decree. Although the proclamation of socialism in the absence of an appropriate economic basis is an act of voluntarism and even opportunism; the same can be said about attempts to solve the ecological problem in this way.

This is clearly reflected in the writings of the eco-socialist Michael Löwy. One of his pamphlets is being actively disseminated by the Trotskyist Social Democrats from the «Anticapitalistas» movement, which has now become an internal trend in «Podemos»:

«Struggle for eco-social reform can give impetus to change, a “transition” between minimum requirements and maximum program, provided that such struggles reject arguments and pressures of dominant interests, appeal to market rules, competitiveness or «modernization».

<…>

-Promotion of public transport – trains, metro, buses, trams – well organized and free of charge, as an alternative to traffic jams and pollution of cities and fields due to private cars and transport infrastructure systems.

– Fight against the debt system and “ultra-neoliberal attitudes” imposed by the IMF and the World Bank on the countries of the South and with serious social and environmental consequences, such as mass unemployment, destruction of social protection and living cultures of indigenous peoples, destruction of natural resources for export.

– Protecting human health from air, water, groundwater or food pollution due to the greed of large capitalist companies.

“Reducing working hours as a response to unemployment and as a vision of a society that prefers free time to the accumulation of benefits and goods.” (Michael Löwy, “What is Eco-Socialism?”, 2004)

One of the claims of this eco-socialism is to abolish external debt and resist globalization. Is this an effective struggle against capitalism and its inherent destructive form of relations with the environment? Not at all, unless you are fascinated by the thesis of third worldists, alternative globalists and environmentalists.

The international division of labour – an economic theory that condemns non-industrial countries to specialize in the production of raw materials or light industry to supply the imperialist countries – combined with the export of capital leads to another very well-known phenomenon – external debt. This has already been shown on the basis of indisputable data by the Albanian Marxist-Leninists:

«Albanian Marxist-Leninists stressed that neo-colonialism cannot be separated from external debt, which grew in huge proportions during the 70s and 80s, as exemplified by the debt of Latin America, which grew from $ 33 billion to $ 360 billion between the years 1973 and 1984. Marxist-Leninists pointed out that this debt destabilized the entire economic system of the region and violated its economic independence. <…> Unlike alternative-globalists and other petty-bourgeois trends, for whom such debt is not inevitable, but the result of deliberate decisions, the result of a “neoliberal” policy, Marxist-Leninists, on the contrary, saw the debt crisis as the result of objective mechanisms of international market production” ». (Vensan Gouysse, «Imperialism and anti-imperialism», 2007[9])

Thinking like alter-globalists or anti-globalists do is to resist reality itself. Improving lending selection, public control over foreign trade, increasing efficiency, reducing corruption in public institutions, reducing the degree of specialization of private companies, reducing illegal capital outflows, actively introducing moratoriums on foreign debts, establishing state bodies to control the illegal import of foreign currency – all these the recipes for the economy have the character of petty-bourgeois radicalism. This approach does not offer valid solutions to the problems described.

In fact, this approach, oblivious to key factors, is as far removed from Marxism as possible. The real causes of the economic crises and the debt enslavement of the former colonial countries, now practically neo-colonies, as well as the mortification of the environment, are due to other factors, much more tangible and noticeable than the wrong decisions of governments, market fluctuations or simple coincidence.

The real reasons lie in the plane of more general issues, such as the most important fact that not only the economic basis but also the capitalist superstructure remains intact:

«The debt crisis is not a sudden occurrence; on the contrary, its roots lie deep in the economic base of these countries. <…> The invasion of the capital of the neocolonialists into the former colonies and dependent countries is directly related to the development and increasing activity of transnational corporations. <…> They play an important role in managing the economy of the former colonies and dependent countries, increasingly subordinating them to the mother country. <…> It should be remembered that many countries that proclaimed their political independence did not encroach on the position of foreign capital in their economies. Thus, in many cases, the old financial systems have survived. <…>

They retain both their specialization in raw materials and agricultural products, the prices of which are either increasing or decreasing, as well as their complete dependence on final products imported from the metropolis, the prices of which tend to rise. <…> The lagging behind of the productive forces in these countries persists, the structural disproportionality in the economy is aggravated, prices in international trade are rising, that is, the plundering of the wealth, labour and sweat of the peoples of the former colonies and dependent countries by imperialist powers is becoming more and more intensive». (Lyulzim Khan, «External debts and imperialist loans, strong links in the neo-colonial chain that enslaves the people», 1988)

Today, eco-socialist groups or parties influenced by these ideas tend to ignore the real causes of existing problems and end up teaming up with the authorities responsible for the policy.

Such political organizations, despite their rhetoric, demonstrate a submissive conciliatory stance towards liberalism, the European Union and transnational corporations, both in power (look at the examples of SYRIZA and Podemos), and without it. This shows that these ideologies and movements cannot guarantee a model in which the problems of ecology and the environment will be finally solved. Especially when their banners are coloured with ideological eclecticism.

Eco-socialist Jorge Richman admits:

«This project cannot reject any of the colours of the rainbow: neither the red of the egalitarian anti-capitalist labour movement, nor the purple of the struggle for women’s liberation, nor the white of the nonviolent movements for peace, nor the anti-authoritarian black libertarians and anarchists, and even more so the green colour of the struggle for the just and free humanity on an inhabited planet».(Jorge Richman, “Socialism will only come by bicycle”, 2012)

In this regard, one cannot fail to mention the “Frankfurt School”. Authors such as Adorno, Fromm, Marcuse, and Horkheimer, who presented themselves as the middle path between Marxism and other ideological currents, such as Freudianism, left us with a mistaken analysis of society. Their analysis is now quite alive within the framework of the mainstream culture, and not accidentally, but for the reason that the bourgeoisie used this Marxist posturing to propagate such ideas as actively as possible and thus neutralize the revolutionary movement of the working masses.

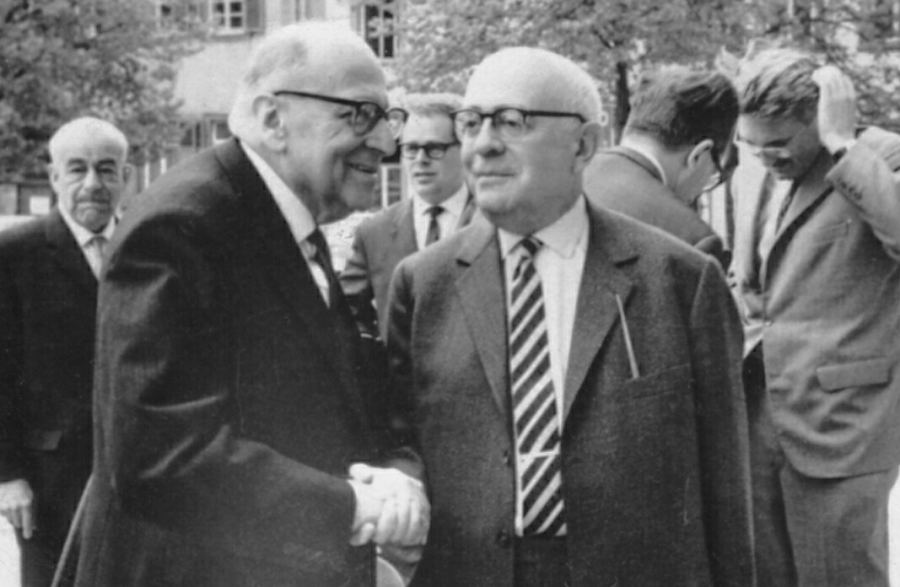

Max Horkheimer (left), Theodor Adorno (right) and Jürgen Habermas (right in the background) in Heidelberg, 1965

They believed that in an industrial society, only the instrumental mind or subjective mind seeking success and efficiency is taken into account, and its goal is the unlimited exploitation of nature.

To eliminate this problem, the “Frankfurt School” actually does not depart from the schemes already proposed in Marxism: a person should not be subordinated to science and technology in a passive form with the indisputable dominance of nature, on the contrary, human will uses technology, but with the knowledge that this use should not go beyond the satisfaction of basic needs.

Where the “Frankfurt School” fails miserably is in its skeptical statements about lack of faith in objective laws and the ability to predict in what form the transformation of society should take place and what steps need to be taken to achieve it. Everything is left at the mercy of freewill under a standing ovation to any statement that goes “against the tide”, especially if it is accompanied by beautiful words.

Thus, the “Frankfurt School” slips into a criticism of individualism, mysticism and irrationality of the feudal-bourgeois society, but has no idea what the social and political model wants to see. Therefore, the pinnacle of their reasoning was the accusations of liberalism and its propaganda in the so-called “totalitarianism” (moreover, the thesis of this concept that Nazism and “Stalinism” are twins, became the ideal ground for strengthening anti-communist propaganda).

In undertaking a study of the state, which is closer, rather, to anarchism than to Marxism, they deny that the state is the apparatus of the rule of one class over another, and limit themselves to utopian howls about its liquidation without further reflection. In a political sense, the Frankfurt School does not have a serious line, it mixes social democratic concepts with the concepts of anarchism, hippies and utopianism.

Another feature that clearly distinguishes this pseudo-Marxist trend from Marxism itself is the ignorance of the economic aspect, the central ridge in understanding any human condition or how the existing production system should be overcome. All this idealism with its vague perspectives was reflected in the political movements of May ’68 and the slogan “All Power to the imagination!”

In the field of economics, they also cannot agree on whether it is necessary to liquidate private property as such or only part of it. Some promote small-scale private property, while others believe that a stroke such as factory committees with the participation of workers will resolve class contradictions in society.

In the field of culture, this school welcomes any cultural trend that, within the framework of capitalism, is supposedly going “against the stream.” For example, Adorno supported the absurd and extravagant directions of musical creativity only because they went against the current, as they say now, against the “mainstream”. This is not revolutionary, but idealism and utopianism, a waste of energy, because much in this “counterculture” is useless and often it turns out to be infected with bourgeois and petty-bourgeois forms of thinking and action.

But the ideologues of the Frankfurt School did not think about whether this “counterculture” corresponds to the aspirations of the workers for the desired social model, or whether it leads them to fruitless methods of struggle against capitalism. These authors simply approach the problem in terms of quantity, mass character. In cultural criticism, their analysis focuses on quantity rather than quality. Their opposition to mass culture is a metaphysical claim based on the belief that anything mass is by definition negative. In reality, mass culture is highly negative only in a society based on private property, on a dehumanized culture, as they themselves say. However, in a society based on socialist economics and politics, culture can spread and be a cure for the millions of poisoned people who were fed this poison in a capitalist society.

Such a mistake from the point of view of assessing the role of mass culture leads, as already mentioned, to a misunderstanding of the relationship between the economic base and the superstructure in various societies.

It would not be superfluous to say that this trend also denies the process of pauperization, that is, the impoverishment of the population, in capitalist society. For these thinkers, all classes are gradually “equalized”, up to the “elimination of class differences”, thanks to the so-called scientific and technological revolution, which, as the historical process has shown, is the complete stupidity of charlatans in the service of big business.

These authors said that due to technological progress and improved access to certain food, educational and health services (which happened gradually in all historical eras and in all economic systems as technological advances normalized and continued to be speculated on, to cool the fervor), the proletariat as such ceased to exist. This is how the Marxist theory of the class struggle is simply toppled on its shoulder by the mere question of technological progress.

This makes as much sense as if we say that progress made the slave, less a slave in antiquity, or that the serf ceased to be a serf with the advent of cheap and affordable food, or that the small peasant was less oppressed because in the era of nascent capitalism there were new devices and methods of farming have been invented.

This theory cannot be understood without knowing the context in which its authors, who mostly lived in developed capitalist countries, in a “consumer society” and were influenced by various theories, developed their ridiculous ideas.

Their concepts indicate a lack of understanding of the fact that in order to provide workers in developed countries with such improvements (yet insignificant in comparison with the capital that could be spent on this), it was necessary to squeeze external borders and third world countries through thousands of mechanisms. Not to mention the preservation within the system of wage labour (generating the proletariat as such), in which it sells its labour-power, from which surplus-value is derived.

On the other hand, this in itself is the result of a misunderstanding of how capitalism functions at the stage of imperialism. As we know, the developed countries are ruled by large monopolies, in contrast to the backward countries and countries dependent on foreign capital, have much more “surplus” capital in circulation. There are so many of them that it helps to smooth out social contradictions: to bribe some of the workers and create a “labour aristocracy”, improve the position of the poorest workers, like by developing a system of social assistance.

However, as Hoxha said, although they “wear nylon clothing produced by the consumer society, in fact they remain the proletariat.” This does not exclude the process of pauperization, which nowadays manifests itself in developed countries in the form of various crises.

In fact, the process of accumulating wealth by oppressing the doomed to poverty is not devoid of linkages with other problems, such as the wasteful use of resources that harms the environment. Both are happening for the reason that capitalism is a greedy and inhumane model.

Neither a consumer society nor improved sanitation or electronics have solved and will not solve the problems of unemployment, the environment, or the overproduction crises under capitalism in the future. This speaks of more than ever the clear relevance of the concept of the proletariat and Marxist theory.

Representatives of the Frankfurt School talk about “dehumanization under capitalism” (which is also transferred to the “experience of communism”). Of course, this is the capitalist system, no one doubts it, but the reason for this is not technological advances, but the private ownership and speculative use of these achievements (just look at its manifestation in industries such as pharmaceuticals or the food industry). The problem, ladies and gentlemen, is the private ownership of the means of production that exists under capitalism, and that it turns even health and food into a commodity. Under the rule of the law of value, this is the norm, which can only lead us to the dead-end that we know about: rich and poor, privileged users of innovation and outcasts who will never enjoy the fruits of progress.

If these writers had sought to understand the dynamics of capitalism, they would have come up with better solutions. But, since they were not interested in economics, but only in their own subjective ideas, they came to the well-known measures to solve the problem of large technological development. Such were, for example, the picturesque – in the spirit of hippies – the proclamation of “a great de-industrialization and return to the countryside.” Some even promoted “destroying machines” because “technology itself dehumanizes,” a view more suited to some ignorant Amish religious sect than an educated and progressive person. It is impossible to reverse the course of history, and they are going to decide everything by willpower and idealism.

Finally, some ideologues, influenced by these theories and existentialism, believed “the inevitable extinction of man as the only thing that can save the planet.” This again has more in common with the approaches of Nietzsche and misanthropy than with any serious progressive position.

If there is a doctrine consisting in the rational use of the productive forces and in the introduction in the modern era of the ideological education of virtuous producers, preceding a cold technical education, then this is Marxism, even if its enemies insist on the opposite.

On the other hand, the Frankfurt School denies the ascending role of the proletariat in history as the class that is to lead the process of overcoming capitalism. They shouted that under the influence of the mass media the alienation among the proletariat in the countries of the “consumer society” had become so great that it became bourgeois and was no longer capable of being the decisive subject of transformations. Thus, some writers ended up calling intellectuals, or even lumpen, the avant-garde, the social stratum that would play the role of the defining or rising class, a complete departure from theory for a number of reasons.

1) A significant part of intellectuals under capitalism cannot survive without serving those who pay them, that is, the bourgeoisie. In addition, intellectuals are a social stratum that includes people from various social classes. Most of them come from wealthy strata, they are very far from the severity of physical labour, which is why they risk moving away from the proletariat, but they are still able to assimilate its theory and maintain ties with it.

2) Lumpen is usually an opportunist element, devoid of any ideological and moral principles, it is mainly a strikebreaker [16] and a hooligan who survives by serving the bourgeoisie. It combines the worst vices of bourgeois society, which in fact uses its way of thinking and acting to achieve the degradation of workers, especially working youth, by spreading Lumpen culture in the media to neutralize the revolutionary labour movement.

3) The working class is the only class that, based on its place in the production system, ensures its reproduction as capitalism expands. It does not decay, like other strata, such as the petty bourgeoisie. Its lack of means of production and its concentration in labour zones lead to the unification and solidarity of its members. The role they play in production gives them a decisive position, containing a great danger to the bourgeoisie if they rise to fight.

The fact that it is deprived of any ownership [of the means of production] leads to the fact that unlike other – old – classes that have fought for power throughout history, the working class needs power not to confirm its power and property, but for the liberation of people from the exploitation of man by man. Along with this, the proletariat is the only social class that has a scientific doctrine (Marxism-Leninism), which leads to the fact that the working class is the undeniable vanguard of the destruction of capitalism.

4) Alienation is not an exclusive phenomenon of capitalist society. It already existed in the feudal and other systems, only it manifested itself differently. The working class can fight back this alienation by uniting, deepening its doctrine, analyzing and showing the causes of pressing problems and proposing revolutionary solutions.

And although the working people, the proletariat, have a largely low level of political consciousness, the bourgeoisie still finds it very difficult to mask contradictions. The proletarian can understand that it is not them who possesses the means of production, but instead, it’s the bourgeois who does.

- One knows very well that if they lose their job, ones ability to work will depend on whether another bourgeois needs them, and neither appropriate working education, nor long work experience guarantees one the right to work.

- One realizes that professions are not paid according to their importance, and, for example, one may receive a ridiculous salary in terms of time and effort spent on labour, and someone else from another specialty or even just a superior worker – three times more.

- One is well aware that if they commit an offence, justice will be different from that applied to the rich.

- One is well aware that the politicians in power or running for office are not from their social class.

- Experience tells one that it is not the rich who pay the price for crises, even when a crisis is triggered by speculation and outright corruption, the workers always pay for it.

All this spontaneously pushes the proletariat, whether you like it or not, towards the class struggle, and those who have realized the situation towards anti-capitalist perspective.

Another important point, in the absence of such subjective factors as the organization of the proletariat and the study of the Marxist-Leninist doctrine, under the constant ideological pressure of the bourgeoisie and its agents, the goals are not achieved, and the proletariat goes astray.

On the other hand, the so-called Frankfurt School had a strong influence on the movements of May 68, on the very emergence of hippies, Eurocommunism and postmodernism. In fact, the Frankfurt School played the role of the “fifth column” within Marxism.

The so-called eco-socialism, as already mentioned, is a mixture of reformism, petty-bourgeois feminism, anarchism and everything that can be added to this “cocktail”. A cocktail that, in fact, is by no means aimed at preserving the environment, but at preserving the current order, including with respect to the environment. Eco-socialism tends to deny the true nature of the state, extol bourgeois democracy and its mechanisms, believe in and participate in “peaceful transformation within the European Union”, deify small private property and the cooperative form as some suitable model (a kind of “capitalism on a smaller scale”) and even accept the existence of capitalist monopolies if they commit themselves to paying taxes and caring for the environment.

Within the framework of the so-called “ecosocialism” socialism in the Marxist sense (the only really existing socialism, while everything else is inevitably capitalism) is impossible, real control over what causes the ecological problem is impossible.

As a result, all these movements can count on, if they come to power, are regrets about the unfulfilled – despite good intentions – environmental hopes. Because they never tried to solve the problems of capitalist production relations and labour exploitation.