We bet you watched some bloggers, who claim to be “communist”, yet know nothing in the Marxist theory. How would Marx react to such “agitators”? We present you an excerpt from the “Extraordinary Decade” by Pavel Annenkov – a Russian literary critic, who lived in the middle of the XIX century and wrote memoires about the meeting of Marx and Engels with Weitling – a preacher of utopian communism.

“…On my first meeting with Marx, he invited me to attend a conference scheduled for the following evening with the tailor Weitling who had a rather large following of workers back in Germany. The conference was being called in order to determine, insofar as possible, the overall mode of operation among the leaders of the workers’ movement. I unhesitatingly accepted the invitation and came to the meeting.

The tailor-agitator Weitling turned out to be a fair-haired, handsome young man, wearing an elegant style of surtout and a coquetishly close-cropped beard, looking more like a traveling salesman than the stem and wrathful zealot I had presumed I would meet. Quickly exchanging greetings, with an added touch of exquisite politeness on Weitling’s part, we sat down at a small green table at one narrow end of which Marx placed himself, pencil in hand and his leonine head bent over a sheet of paper.

Wilhelm Christian Weitling (October 5, 1808 – January 25, 1871)

His inseparable companion and colleague in propaganda, the tall and erect Engels, with his British air of dignity and gravity, opened the meeting with a speech. In it he spoke of the necessity for people dedicated to the cause of trans¬forming labor to expound their common views and establish one overall doctrine which would serve as the standard for all their followers who had neither the time nor the opportunity to concern themselves with theoretical issues.

Engels had not yet concluded his speech when Marx looked up and addressed a question directly to Weitling: “Tell us, Weitling, you, who have made such a rumpus in Germany with your communist preachings and have won over so many workers, causing them to lose their jobs and their crust of bread, with what fundamental principles do you justify your revolutionary and social activity and on what basis do you intend affirming it in the future?”

I remember the actual form of this trenchant question very well because it began a very heated debate among the conference participants which lasted, however, as will be shown, but a very short time. Weitling apparently wanted to confine the conference to the platitudes of liberal colloquy.

With an expression on his face suggesting earnestness and anxiety, he began to explain that his aim was not to create new economic theories but to make use of those that were best able, as experience in France had shown, to open the workers’ eyes to the horror of their situation and all the injustices that had, with regard to them, become the bywords of governments and societies, to teach them not to put trust any longer in promises on the part of the latter and to rely only on themselves, organizing into democratic and communist communes. He spoke at length but, to my surprise and in contrast with Engels’ speech, diffusely, not altogether literately, repeating his words and often correcting them, and experiencing difficulty in coming to conclusions which either were made belatedly or came ahead of the arguments for them. He had a far different audience now than the one that usually crowded around his work bench or read his newspapers and printed pamphlets on contemporary economic practices, and, in consequence, he had lost the facility of both his thought and his tongue.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

Weitling likely would have talked even longer, if Marx, his brows angrily knit, had not interrupted him and begun to voice his objection. The gist of his sarcastic speech was that to arouse the population without giving it firm and thoroughly reasoned out bases for its actions meant simply to deceive it. The stimulation of fantastic hopes that had just been mentioned — Marx observed further on — led only to the ultimate ruin, and not the salvation, of the oppressed. Especially in Germany, to appeal to the workers without a rigorous scientific idea and without a positive doctrine had the same value as an empty and dishonest game at playing preacher, with someone supposed to be an inspired prophet on the one side and only asses listening to him with mouths agape allowed on the other. “Look here,” he added, suddenly jerking out his hand and pointing at me, “we have a Russian with us. In his country, Weitling, your role might be suitable: there, indeed, associations of nonsensical prophets and nonsensical followers are the only things that can be put together and made to work successfully.” In a civilized country like Germany, Marx continued, developing his idea, people could do nothing without a positive doctrine and, in fact, had done nothing up to now except to make noise, cause harmful outbreaks, and ruin the very cause they had espoused.

The color rose in Weitling’s pale cheeks and he recovered his genuine, fluent speech. In a voice quivering with emotion he began to argue that a man who had gathered hundreds of people together in the name of the idea of justice, solidarity, and brotherly mutual aid under one banner could not be called a vain and worthless person, that he, Weitling, consoled himself in the face of the day’s attacks with the recollection of the hundreds of letters and expressions of gratitude he had received from every comer of his fatherland, and that his modest, preparatory work was, perhaps, more important for the general cause than criticism and closet analyses of doctrines in seclusion from the suffering world and the miseries of the people.

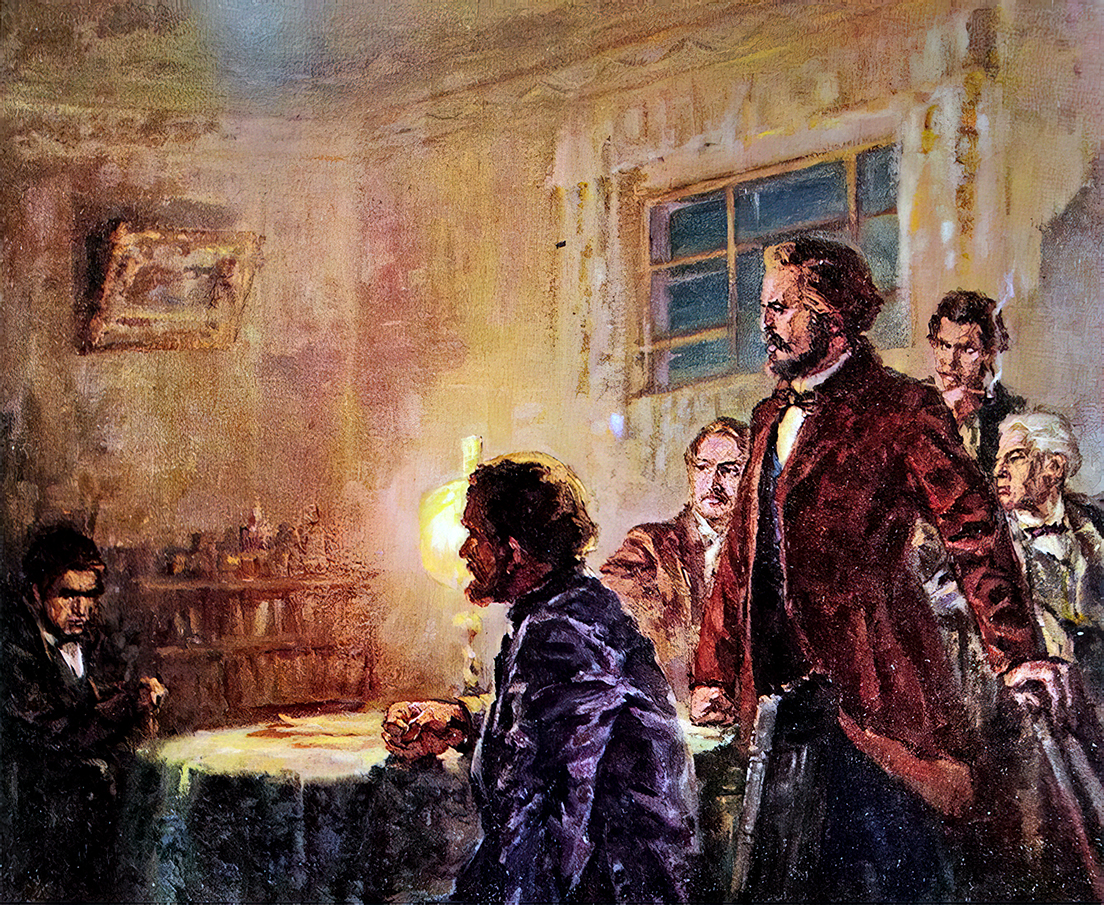

Marx (on the right), Engels (behind Marx), Weitling (on the left) and Annenkov (on the right, behind Marx, smoking) portrayed by the Chinese artist Gāo Mǎng.

On hearing these last words, Marx, at the height of fury, slammed his fist down on the table so hard that the lamp on the table reverberated and tottered, and jumping up from his place, said at the same time: “Ignorance has never yet helped anybody!” We all followed his example and also got up from the table. The meeting had ended. While Marx paced the room back and forth in extreme anger and irritation, I hastily bid him and his companions good-bye and went home, astounded by everything I had seen and heard…”