Trump’s return to the White House and the escalation of the trade war have triggered a new stage in the confrontation between the US and China. Having grown into a powerful industrial nation thanks to foreign capital, China is now challenging the hegemony of American corporations, building its own trade networks, and increasing its military potential.

This rivalry is a clash between two leading centers of the capitalist system for control over global resources, markets, and production – a conflict in which compromise is impossible. Along what lines is the US-China struggle unfolding? Does it threaten a new world war? And are the Chinese and Americans ready to kill each other?

I. Why Does China’s Rise Threaten the USA?

1.1. The US-Centric World Order

Over the past 30-40 years, China has transformed from a backwards, closed, agrarian country into one of the world’s leading economies, a strong and influential center of the global capitalist system. In half a century, China’s nominal GDP has increased fortyfold, and for about a decade the country has ranked second in the world by this measure. The growth of industrial production, capital exports, the subjugation of new markets for goods and capital investment, active militarisation, and the expansion of influence over other countries have brought China into conflict with US interests and have eroded Washington’s former position as the undisputed hegemon of the capitalist system.

By the 1980s, the United States of America already held a leading position in the global imperialist system as the largest economic and military power. Their consolidation as the world hegemon was completed after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, which marked the end of the Cold War and established the USA as the sole superpower. After the USSR’s dissolution, the countries of the former socialist bloc fell entirely under the influence of American capital.

In the 1990s, the USA’s economic leadership was reflected in a number of key indicators:

- In 1990, the USA’s GDP amounted to $5.96 trillion in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, which significantly exceeded the figures of other countries. For comparison, Japan, which ranked second, had a GDP of $2.46 trillion, less than half as small. By the beginning of the new millennium, the USA’s share of global GDP consistently stood at around 25–30%.

- The USA was the largest source and recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI). Throughout the 1990s, between 20-25% of global FDI originated from the USA, while between 15–27% was absorbed by it.

- The USA accounted for between 20-25% of global industrial output. Such a powerful industrial base served as the economic foundation of the USA’s global leadership.

All of this contributed to the formation and consolidation of a USAcentric world order, the state of the modern capitalist system in which the USA was the unquestioned leader, and American capital was the most powerful force on the planet. This position was reinforced by several instruments: the dollar as the world’s currency, international financial and trade institutions, military power, and NATO.

The Dollar as the World Currency

After the introduction of the Bretton Woods system in 1944, the dollar became the main world currency, the predominant means of international payments and wealth accumulation. In 1971, Richard Nixon ended the dollar’s gold convertibility, and from that moment, the dollar was effectively backed directly by the economic power of the USA and its reputation in global markets.

Since the 1970s, oil transactions by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and others have been conducted predominantly in dollars, forcing countries to hold vast reserves in US currency. According to the International Monetary Fund, in 2000, 71% of the world’s foreign exchange reserves were held in US dollars. By 2021, this figure had decreased to 59%, which nevertheless still demonstrates the dollar’s continued dominance.

The dollar’s status gives the USA the ability to influence the global financial system through sanctions and control over the SWIFT interbank payment system. Although SWIFT is formally neutral, most of its transactions are conducted in dollars. This means that in the event of a global conflict or political crisis, the USA has the ability to disconnect a particular country from SWIFT as a form of economic pressure, effectively isolating it from international financial operations.

There are several examples of SWIFT being used as a tool for sanctions:

- In 2012, as part of sanctions against Iran’s nuclear program, the European Union decided to disconnect several Iranian banks from SWIFT. This led to significant economic costs: Iran lost about half of its oil export revenues and a substantial portion of its foreign trade.

- Following the outbreak of the conflict in Ukraine in 2022, the USA, EU, United Kingdom, and Canada decided to disconnect several Russian banks from SWIFT as part of sanctions aimed at Russia’s economic isolation. As of March 12, 2022, seven Russian banks were removed from the system.

However, the largest banks connected to the energy sector, such as Gazprombank, initially avoided disconnection due to Europe’s dependence on Russian energy resources. In 2024, the USA imposed additional sanctions against Gazprombank, restricting its operations within the American financial system, as well as against more than 50 other Russian banks and Russia’s SWIFT alternative, the Financial Message Transfer System (SPFS).

International Institutions

After World War II, the USA created a global economic system in which it played the leading role, using international organisations to achieve this.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), established in 1944, provides loans to countries in crisis situations, but on terms favourable to the USA. The USA controls 17.43% of all IMF quotas, which gives it 16.50% of the voting power. This share is slightly lower than the quota because part of the votes is distributed equally among all countries. For key decisions such as amending the Articles of Agreement, revising quotas, or granting large loans, at least 85% of the votes are required. Thus, the USA effectively holds veto power: without their consent, reaching this threshold is simply impossible. No other country possesses such a share.

Most often, countries seeking IMF assistance have to pay through privatisation, reductions in government subsidies for domestic production, and general economic liberalisation.

According to studies, from 1990 to 2004, over 80% of IMF assistance programs included conditions for trade and capital liberalisation, 60-80% required privatisation, and 50-70% imposed limits on public sector wages and employment, as well as pension reforms. Ultimately, such policies cleared the way for American corporations to enter the national markets of many countries.

One illustrative example of American capital entering another country through the IMF is Russia in the 1990s. After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Russia, facing a deep economic crisis, became a major borrower from the IMF. From 1992 to 1999, Russia received IMF loans totaling over $20 billion. These loans were provided on the condition of implementing structural reforms aimed at the interests of Western capital: accelerated privatisation of state enterprises, liberalisation of trade and capital, primarily the removal of barriers for foreign capital and reductions in the public sector and social spending.

The IMF’s requirements led to mass privatisation, resulting in a significant portion of state enterprises falling into private hands, often at undervalued prices. This opened the way for American and European corporations to profitably acquire Russian assets. The free movement of capital encouraged speculative investments by Western funds in Russian government short-term bonds (GKOs), which led to a massive capital outflow in 1997-1998 amid the Asian financial crisis. In August 1998, Russia declared default.

By 1998, the poverty rate had reached 30%, social guarantees had been reduced, and labour exploitation had intensified. Trade liberalisation contributed to the establishment of a resource-based economic model: Russia exported raw materials (oil, gas, metals) at low prices while importing high-tech goods and services from the USA and Europe.

The World Bank, established in 1944, finances the development of countries through interest-free loans and grants, but again with conditions favourable to the USA. The United States owns 15.87% of the bank’s shares, giving it 15.02% of the voting power. As with the IMF, key decisions require 85% of the votes, effectively giving the USA veto power. Additionally, by tradition, the President of the World Bank is an American, appointed by the USA and approved by the Board of Directors.

Like the IMF, since the early 1990s, the World Bank has promoted the “Washington Consensus” in other countries through loans and grants, which involves imposing policies of market reforms, privatisation, and reductions in government regulation. Both institutions effectively pursue two goals: to protect American capital and investments abroad, and to create conditions for their most profitable development in the borrowing country. Furthermore, the borrowing country becomes economically dependent on the USA, which also results in political subordination.

Like the IMF, the World Bank financed Russia in the 1990s. From 1992 to 1999, the country received loans and grants totaling around $12 billion from the World Bank, including projects for structural economic reforms, infrastructure development, and support for the private sector.

World Bank loans in 1992-1994 were tied to the acceleration of privatisation in the oil and gas, metallurgical, and energy sectors. This allowed Western corporations, including American ones (such as ExxonMobil and Chevron), to acquire Russian industrial assets either directly or through oligarchic groups at undervalued prices.

The World Bank’s projects for reforming the coal industry included the closure of unprofitable mines and the privatisation of the remaining ones, which opened the sector to foreign investors, primarily Western.

The World Bank’s conditions included reductions in budgetary spending and economic deregulation. Loans for public administration reform required cuts to social programmes, which led to the deterioration of healthcare and education, as well as rising poverty. With the support of the World Bank, financial sector reforms were carried out in Russia that opened the doors to Western banks such as Citibank and JPMorgan. They quickly occupied market niches by servicing privatised companies and oligarchic structures.

The World Trade Organization (WTO), established in 1995, regulates global trade by developing trade rules, facilitating trade negotiations, and resolving trade disputes. The USA is among the largest contributors to the WTO budget: in 2023, its contribution accounted for 11.3% of the organisation’s total budget, which includes 164 member countries.

The USA has also been a leader in promoting numerous standards and initiatives within the WTO. One of its most significant achievements was the inclusion in the WTO agreement of the standard on intellectual property protection, known as TRIPS (Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights). This agreement, initiated by the USA a year before the WTO officially came into force, was aimed at strengthening the protection of patents, trademarks, copyrights, and other aspects of intellectual property.

The impact of TRIPS was particularly evident in the pharmaceutical industry. American pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and Merck secured protection for their patents against competition from cheaper Indian generics, which allowed them to monopolise the market for a number of medicines in developing countries.

Through the WTO, the United States also achieved reductions in agricultural tariffs in countries such as India, Brazil, and China. These countries were also required to reduce domestic subsidies for their agricultural producers.

In the 1990s, the USA, through the WTO and the World Bank, facilitated the opening of China’s economy, counting on its dependence as a factor that partly shaped the subsequent dynamics of global relations.

When joining the WTO, Russia committed to reducing its average weighted import tariff from 10% in 2011 to 7.8% by 2015, and for certain goods (such as cars and electronics) to 5-6%. According to a WTO report, Russia also reduced nontariff barriers such as quotas and licences. This made the market more profitable for Western goods, especially high-tech and consumer products produced by American and European companies, such as Apple, General Motors, and Procter & Gamble.

Military Power and NATO

The United States Armed Forces is one of the largest and most technologically advanced militaries in the world. They comprise about 1.32 million active-duty service members, 738,000 reservists and National Guard personnel, and 754,000 civilian employees.

Since the 20th century, the United States has annually spent more on defence than the ten largest competitors combined. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, its share of global military expenditures remained the highest, reaching roughly one-third of total spending.

In 2025, Donald Trump proposed a record military budget for the next fiscal year of $1.01 trillion. This is 13% higher than the current expenditure of $883.7 billion. According to estimates, with the U.S. GDP at $28–29 trillion, defence spending would account for about 3.4-3.5% of GDP, which is comparable to the 2023 level (3.36% of GDP according to the World Bank).

The United States is the undisputed leader in terms of global military presence. It maintains more than 750 military bases across 80 countries, at least three times more than all other nations combined. The U.S. also leads the race in military technology: in 2020, spending on military research and development reached $104 billion, absorbing a significant share of the entire federal R&D budget. Added to this arsenal of power is the world’s second-largest nuclear arsenal of about 3,708 warheads, either deployed or held in reserve.

The United States not only possesses the world’s most powerful military but also uses NATO as a tool to pursue its military ambitions, drawing on the resources of other countries.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), established in 1949, was originally positioned as an alliance against the Soviet Union. However, after the collapse of the USSR in 1991, it did not lose its significance, continuing to serve as a tool for expanding American military presence.

Since 1999, NATO has grown from 16 to 32 member countries, expanding its borders into Eastern Europe. Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary joined the alliance in 1999, followed in 2004 by the Baltic states, Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia. This expansion was accompanied by military operations: the bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 (Operation Allied Force), the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, and the intervention in Libya in 2011. The most recent members to join NATO were Finland in 2023 and Sweden in 2024.

The United States controls NATO through its dominant military, financial, and political influence. The U.S. contributes 16% of NATO’s direct budget and covers a large portion of the indirect costs associated with maintaining military bases and conducting operations. The Supreme Allied Commander Europe – the head of NATO’s combined forces in Europe – has always been an American general (since 1951). NATO decisions most often reflect U.S. priorities: eastward expansion in the 1990s, operations in Afghanistan after 9/11, the military campaign in Syria in the 2010s, and others.

The organization provides the United States with the ability to influence the decisions and policies of other member countries, as well as those seeking to become NATO members or partners. The USA uses this organization as a lever of military and political pressure. A clear example: Russia and Ukraine.

Ukraine, as a country seeking NATO membership, is an important example of how the United States uses the alliance to pursue its own policies. Ukraine began aspiring to join NATO under the influence of Western capital, which, through economic pressure (IMF and World Bank loans), political manipulation (support for nongovernmental organizations, legitimization of the 2014 coup), and military assistance (training of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, arms supplies), subordinated Ukraine’s ruling class to its interests.

This was used to weaken Russia’s influence in the post-Soviet space. After the pro-Russian ruling circles in Ukraine were removed in 2014, Ukraine became a tool for exerting pressure on Russian capital and its political ambitions. The militarization of the country under the pretext of its potential NATO membership became a key element of the U.S. strategy to contain Russia in the region. The supply of Western weapons, including Javelin anti-tank systems, and training of the Ukrainian Armed Forces according to NATO standards temporarily restrained Russia’s ruling class. Joint exercises, such as Sea Breeze and Rapid Trident, conducted near Russian borders, reinforced this policy. Ukraine officially enshrined its course toward NATO membership in its Constitution in 2019, symbolically cementing its role as an instrument of U.S. pressure on Russia.

With the outbreak of the special military operation in 2022, the United States used Ukraine as a proxy to weaken Russia militarily and economically. Large-scale arms supplies (HIMARS, Patriot, Leopard tanks) and financial assistance worth hundreds of billions of dollars made Ukraine dependent on NATO, while simultaneously depleting Russian resources in the protracted conflict. The conflict in Ukraine allowed the USA to consolidate its influence in the region and strengthen Eastern European countries’ dependence on American military and economic support.

Thus, economic supremacy, reinforced by dollar dominance and the influence of international institutions, combined with the largest military forces and NATO, has enabled the United States to establish control over global economic and political processes. At the same time, this has ensured the dependence of other countries and the central role of American capital in the global capitalist system.

China’s Claims to Hegemony

Until the 2010s, the position of the United States was indisputable. However, by this point, China’s growing capital began to pose a threat to the U.S. China’s rise has largely been driven by economic cooperation with the United States, which makes the situation somewhat paradoxical for American foreign policy, yet predictable within the capitalist system as a whole.

From 1990 to 2015, according to the Rhodium Group and the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations, American companies invested approximately $228 billion in China, completing around 6,700 deals. In addition to direct investments, U.S. companies brought advanced technologies that had not previously been widely available in the country: high-tech equipment, software, engineering solutions, and production methods. Moreover, 71% of U.S. FDI in China was in greenfield projects, i.e., projects involving the creation of physical infrastructure, factories, warehouses, and production facilities from scratch.

This transfer of technologies and economic processes led to a qualitative leap in Chinese industry: it shifted from manual labor and outdated methods to automated, standardized, and globally competitive production. American investments became not just a source of capital but a catalyst for China’s technological and industrial transformation, contributing to the growth and establishment of Chinese corporations.

And now, having grown on the investments of American corporations, China began to be seen by the United States as a threat to the entire system of the U.S.-centered world order that had existed until then. For the first time at the official level, China was explicitly named a threat to American leadership in the U.S. National Security Strategy of 2017. This was during the first administration of Donald Trump.

In the document, China was designated not merely as a competitor of the United States – a special term was introduced for this: a "revisionist state" (i.e. the state that wishes to revise the current world order), whose policies "directly contradict the interests and values of the United States". Since then, American officials, politicians, and government institutions have regularly reiterated this assessment, calling China the main threat.

The most recent assessment of China is presented in the latest report by the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) dated May 11 of this year. The authors of the report place the PRC at the top of the list of "competitors and adversaries" of the United States and, among other things, state:

"China maintains its strategic objectives: to become the leading power in East Asia, challenge the United States in the struggle for global leadership, reunify Taiwan with mainland China, ensure the development and resilience of the Chinese economy, and achieve technological self-sufficiency by midcentury. China continues to build its global capabilities to counter the United States and its allies in diplomatic, informational, military, and economic spheres. PRC President Xi Jinping will continue to oversee nationwide efforts to enhance China’s preparedness to compete with the U.S. and its allies in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond, as well as targeted efforts to undermine public and political support for U.S. military alliances and security partnerships".

The report examines China’s militarisation and rising defence spending, the modernization of its nuclear arsenal, the growth of its space capabilities, cyber threats posed by China to the United States and Western countries, as well as its policy towards Taiwan. Ultimately, this section of the report is written in the spirit of recognising the intractability of contradictions between the U.S. and China and the inevitability of a direct armed confrontation in the near future.

1.2. The Chinese Alternative

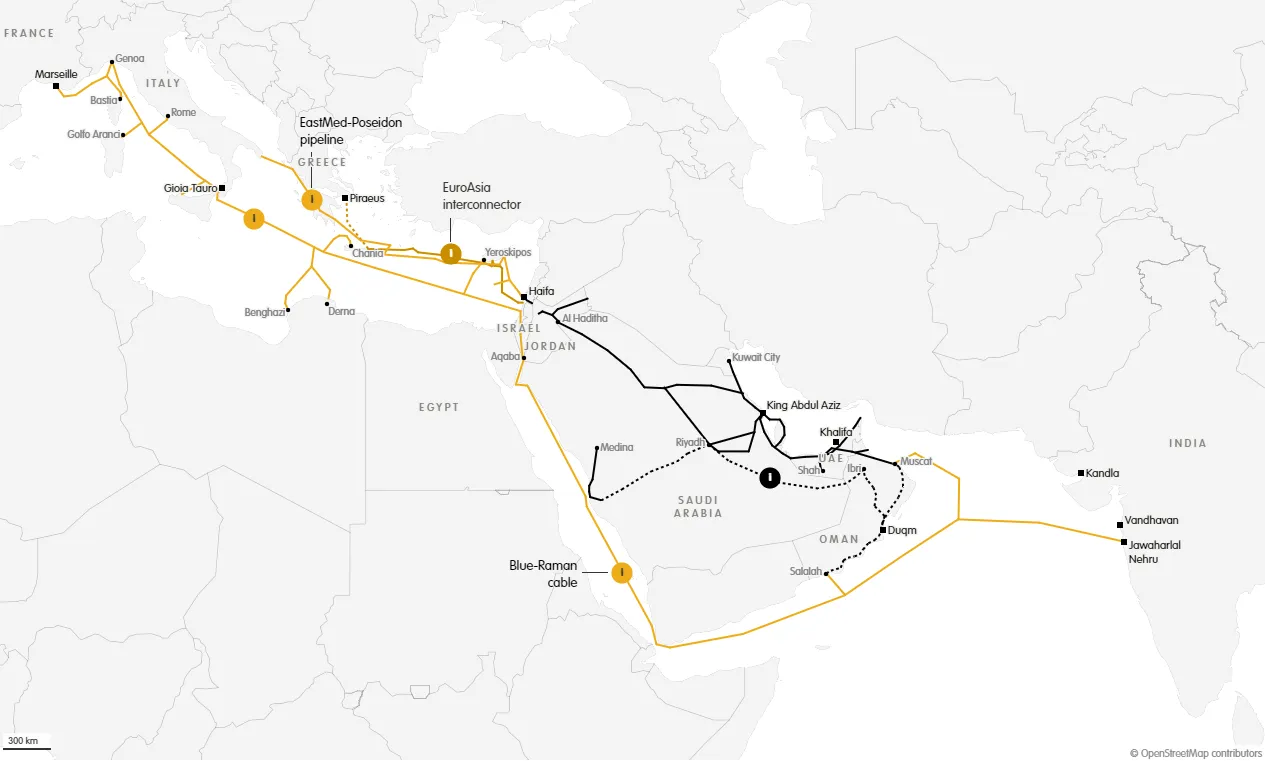

The growth and consolidation of Chinese capital have led to its active export abroad. China has paid particular attention to investing in the infrastructure of other countries. In 2013, the "One Belt, One Road" initiative was launched, aimed at creating a network of transport and trade corridors connecting dozens of countries. This programme not only strengthens China’s economic and political influence but also creates a system of states dependent on Chinese investments.

“One Belt, One Road”

In 2013, China announced the launch of the “One Belt, One Road” project (officially known as the Belt and Road Initiative, BRI). Its aim is to develop infrastructure and trade links between Asia, Europe, Africa, and other regions through investments in transport, energy, and digital projects.

The initiative comprises two main components: the “Silk Road Economic Belt” (an overland route) and the “21st-Century Maritime Silk Road.” In 2014, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was established to support the initiative. Although China is not the bank’s sole shareholder, its stake is about 30%, giving it substantial influence over the institution’s decisions.

In practice, the initiative pursues the following objectives:

- The creation of new trade routes under China’s control.

- The strengthening of China’s economic and diplomatic leverage over other countries.

- The expansion of China’s political influence.

- The international expansion of Chinese companies.

Through large-scale investments in transport networks, ports, railways and energy infrastructure, China is building an alternative global economic system in which Chinese capital and goods occupy a dominant position.

According to Chinese authorities, the cumulative expenditures on the Belt and Road Initiative had exceeded $1 trillion by 2023. As of July 2023, 126 countries had joined the project by signing cooperation agreements with China. The BRI covers roughly 63% of the world’s population and more than one-third of global GDP. By 2023, over 3,000 projects had been implemented under the initiative.

The leading recipients of BRI investments include:

- Pakistan. The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a large-scale infrastructure project connecting the port of Gwadar in southwestern Pakistan with the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in northwest China. The project comprises road and rail links, port facilities, and energy projects, with a total estimated cost of more than $62 billion.

In 2015, China obtained the right to operate the port of Gwadar for 43 years through the China Overseas Port Holding Company (COPHC). The official purpose was the expansion and modernization of the port. In practice, the port’s strategic location near the Strait of Hormuz allows China to influence sea lanes used to transport oil and gas from the Middle East. The port also reduces China’s reliance on the Strait of Malacca, through which about 80% of China’s imported oil passes. - Kazakhstan. Between 2013 and 2020, China invested approximately $18.5 billion in Kazakhstan’s economy under the BRI, of which $3.8 billion went to the transport sector. The total value of joint projects exceeds $21 billion. Kazakhstan is part of several BRI corridors, including the China–Kazakhstan–Russia–Europe route and a southern corridor through Central Asia, Turkmenistan, and Iran to the Middle East. Container traffic through Kazakhstan has increased more than one hundredfold since the project’s launch.

- Indonesia. By 2024, China had invested around $40 billion in Indonesia through direct investments and infrastructure projects.

The most significant Indonesian BRI project is the Jakarta–Bandung high‑speed railway. The project is implemented by the Kereta Cepat Indonesia China (KCIC) consortium, in which Indonesian state companies hold 60% and Chinese partners, including China Railway, hold 40%.

China has also invested heavily in Indonesia’s mining and metallurgical sectors. In Central Sulawesi Province, an industrial park, the Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP), was built where the Chinese company Tsingshan Holding Group produces nickel and steel.

Significant investments have also been made in the energy sector and in port modernization.

The “One Belt, One Road” project, together with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), can be understood as a Chinese counterpart to the IMF and the World Bank. Under the initiative, countries receive investments and loans for development without being required to liberalize their economies or reduce the public sector. This characteristic weakens the political leverage of the United States over participating countries.

Nevertheless, China, like the United States, pursues its own interests through these investments. According to available data, the hidden debts of BRI countries to China have reached $385 billion. Through debt obligations, China exerts political influence on other states.

For example, in 2017, Sri Lanka, unable to repay an $8 billion debt to China, leased the Hambantota port to the Chinese state company China Merchants Port Holdings for 99 years in exchange for a debt reduction of $1.12 billion. China acquired 70% of the port’s shares and control over the surrounding area. We have previously written about this debt trap

Hambantota port is located on Sri Lanka’s southern coast near key Indian Ocean sea lanes. These routes carry about 80% of the world’s seaborne oil trade and 50% of container traffic between Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. Control of Hambantota gives China influence close to India, a regional competitor, and strengthens its position in South Asia.

In 2009, during Greece’s debt crisis, the Chinese state company COSCO acquired 51% of the Piraeus port for €500 million. In 2016, COSCO increased its stake to 67% for €368.5 million. Total investment has amounted to about €1.5 billion. Piraeus, near Athens, is the largest port in the Mediterranean and a gateway to Europe for Asian goods. It lies at the intersection of trade routes between Asia, Europe, and Africa. Piraeus handles some 17 million tonnes of cargo and 3.7 million containers annually, making it a key node in the “One Belt, One Road” initiative.

The project supports the development of China’s western regions and helps address excess domestic production capacity by expanding markets in Eurasia. Chinese corporations gain access to participating countries’ resources. By creating economic dependence through investments and building infrastructure, the PRC strengthens its political influence and brings developing states into a subordinate relationship.

The Development of China’s Military Industry and Armed Forces

China’s military-industrial sector has experienced rapid growth over the past three decades. This expansion is evident both in rising financial allocations and in the development of the technological base. Military spending was under $10 billion in the early 1990s and reached $292 billion by 2023. The U.S. Department of Defense, in its report to the U.S. Congress on Chinese military and defense activities, cites even higher estimates for China’s military budget, between $300 billion and $450 billion. By this measure, China ranks second after the United States. The increase in defense spending has been accompanied by major investments in the defense industry, the construction of new production capacities, and the expansion of scientific and technical potential.

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA), as of 2023, is the world’s largest by personnel: about 2 million on active duty and roughly 510,000 in reserve. The PLA is undergoing active modernization. The share of modern weaponry in its arsenal rose from 20% in 2000 to more than 70% by 2023.

Key achievements of the Chinese armed forces include the development of the fifth‑generation J‑20 fighter, which entered service in 2017, and the substantial expansion of the navy. By 2023, the People’s Liberation Army Navy comprised roughly 370 surface ships and submarines, making it the largest navy in the world by number of hulls. China is also a leader in the production of hypersonic missiles and is developing intercontinental ballistic missile capabilities. China has been increasing its nuclear arsenal as well: from 2019 to 2024, the estimated stockpile grew threefold, from about 200 to around 600 warheads.

The U.S. Department of Defense characterizes China’s military ambitions as follows:

- China seeks the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” by 2049. This objective encompasses modernization across political, economic, social, technological, and military spheres, aimed at reshaping the international order in ways that favor China.

- Chinese military policy is framed around defending sovereignty – particularly regarding Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and Tibet – ensuring security and advancing national interests. By 2049, the PLA is expected to become a “world‑class military.”

- The Department of Defense notes a growing Chinese readiness to use military force to defend “developmental interests” abroad, a stance reflected in amendments to the National Defense Authorization Act of 2020.

In recent decades, China has emerged as one of the world’s leading military powers. Its rapid accumulation of financial, technological, and human resources reflects the ruling authorities’ ambitions to strengthen global influence and attain military superiority by the mid‑21st century.

Penetration of Chinese Capital into Europe

After World War II, Western Europe remained largely under the sway of American capital and investment. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe also came predominantly under the influence of American capital.

By the early 2010s, however, Chinese capital had found opportunities for investment in Europe. By 2016, China had invested roughly €100 billion in European countries, with 59% of that amount directed to the largest economies: the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. Chinese investment activity in Europe peaked in 2016–2017 and then declined sharply.

The primary objectives of Chinese investments in Europe are access to Western technologies and to the European market. From 2005 to 2024, the United Kingdom attracted $104 billion in Chinese investment, according to the China Global Investment Tracker. These investments are concentrated in energy, real estate, technology, and transport.

In the energy sector, China participates in the construction of the Hinkley Point C nuclear power station, the largest nuclear project in the world. Hinkley Point C is expected to supply about 7% of the United Kingdom’s electricity demand. Project costs have reached an estimated £41–47 billion. For China, involvement in this project represents entry to Western nuclear‑technology markets and a strengthening of its position in global energy.

In 2020, the steelmaker Jingye Group acquired British Steel, giving China access to the European steel market and related technologies. In France, Chinese investment has been active since the early 2010s, including Dongfeng Motor’s dealings with Peugeot‑Citroën and the acquisition of Club Med by the Fosun conglomerate.

Germany saw major transactions in high technology: Midea acquired the robot manufacturer Kuka, and ChemChina purchased KraussMaffei, a leader in polymer‑processing equipment. These acquisitions strengthened China’s position as a major producer and consumer of plastics.

In 2018, Geely became the largest single shareholder in Daimler AG, acquiring 9.69% of the company and gaining access to technologies in electric vehicles.

After the trade tensions with the United States began in 2018, Chinese investment in Europe declined overall but focused more on strategic sectors. Between 2020 and 2024, a key destination was Hungary. In 2023, Hungary received 44% of all Chinese investment in Europe. Major projects include BYD’s planned factory in Szeged (announced December 2023) and CATL’s battery plant in Debrecen.

Penetration of Chinese Capital into Latin America

From 2005 to 2024, China invested more than $200 billion in Latin America, according to the China Global Investment Tracker. Unlike in Europe, where China often seeks access to technology, in Latin America, its investments have focused on gaining control of raw materials needed for high‑technology industries, notably for electric‑vehicle and battery production.

About half of the world’s lithium reserves are concentrated in the “Lithium Triangle” (Chile, Bolivia, Argentina). In 2018, the Chinese company Tianqi Lithium acquired nearly 25% of the Chilean firm SQM, gaining access to lithium deposits in the Atacama Desert and increasing its share of the global lithium market from 12% to 15%.

Ganfeng Lithium has invested in Argentine lithium projects since 2020, including the Cauchari‑Olaroz deposit in partnership with the Canadian company Lithium Americas. By 2024, these investments enabled exports of lithium to China of up to 40,000 tonnes per year. In 2022–2023, Ganfeng also negotiated for lithium development in Mexico, but no agreement had been finalized.

China has also invested heavily in copper. In 2014, MMG Limited paid $7 billion for the Las Bambas mine in Peru, the world’s second‑largest copper producer. Under the BRI, China has also invested in infrastructure for transporting natural resources.

A second major area of Chinese investment in the region is power generation and grid infrastructure. In 2017, State Grid Corporation acquired control of Brazil’s CPFL Energia, strengthening China’s position in the energy sector, including renewables. In the same year, China Gezhouba Group began construction of the Condor Cliff and La Barrancosa hydroelectric projects in Argentina, a $4.7 billion program that it financed to the extent of about 85%.

In 2020, China Southern Power Grid acquired roughly 25% of Transelec, Chile’s largest transmission‑line operator, but did not obtain full control of the company. Transelec operates more than 10,000 km of transmission lines that supply power to about 98% of Chile’s population.

1.3. Points of Contact

The threat of cheap, mass-produced Chinese goods

Chinese goods are often cheap and mass-produced, a longstanding threat to American capital. This process is rooted in the fundamental principles of capitalist competition, where cost reduction is a key factor in increasing profits.

Chinese products are inexpensive due to the very low wages of Chinese workers, $6 per hour versus $30-$35 per hour in the United States. On average, Chinese goods are 2-6 times cheaper than American ones, depending on the category: smartphones up to 6 times; clothing 6-12 times; electronics 2-3 times. This price advantage has enabled Chinese producers to displace American products not only on the global market but also within the US domestic market.

At the same time, China produced nearly 29% of the world’s industrial goods as of 2023. Overall, by the measure of value added in manufacturing (which reflects the sector’s economic contribution to the national economy), China surpassed the United States already in 2010.

Chinese products have long held a firm position in the American market. The United States imports 41% of its consumer electronics, 26% of household appliances, and 28% of textiles from China. This abundance of affordable Chinese goods reduces demand for American-made products, forcing US manufacturers to either cut output or move production abroad.

The situation intensified in 2001 with China’s accession to the WTO. Since then, the United States has lost 3.7 million manufacturing jobs, mainly due to the influx of cheap Chinese goods. According to the Economic Policy Institute, three-quarters of the jobs lost from 2001 to 2018 were in manufacturing.

The rise of Chinese influence in the American economy is more than trade competition; it is a struggle for global economic dominance. In 2022, the US trade deficit with China reached $382 billion, reflecting deep integration and interdependence between the two economies: the United States as a consumer, and China as a producer.

On a global scale, this process has systemic effects: American capital is losing control over world and domestic markets, ceding ground to a new center of accumulation in the form of China.

Investment Expansion of China vs. Investment Expansion of the United States

China’s investment expansion inevitably comes into conflict with American capital. Both countries compete for control of resources, technologies, and strategic markets worldwide. This confrontation, which affects both developing and developed countries, reflects not only economic interests but also a deeper struggle for political dominance within capitalist competition.

To illustrate the clash between Chinese and US foreign direct investment in other countries, we will consider the period from 2013 to 2023 and plot the relevant data (foreign direct investment, FDI) on a chart.

We take 2013 as the starting point because that year saw the launch of the “Belt and Road” initiative, which can be considered the beginning of the most active period of Chinese overseas investment. The accompanying chart does not show regions such as Europe and North America, since including them would skew the visualization due to their much larger figures. This data is noted in the chart’s caption.

North America

Chinese investment in the region is concentrated in the United States, primarily in high‑technology assets and strategic markets. After 2017, investment volumes declined due to restrictions. The main sectors are technology (40%), commercial real estate (25%), and energy (20%).

Cumulative US investments in Canada and Mexico amount to $444 billion, mainly in manufacturing (35%), finance (25%), and energy (20%). The United States significantly outpaces China in the region owing to active participation in manufacturing and trade, while China lags because of restrictions.

Europe

China has invested about $215 billion in Europe. Volumes grew until 2018 and then fell because of EU controls. The main sectors are manufacturing (30%), energy (25%), and technology (20%).

Europe remains the largest destination for US FDI; it accounts for roughly 45% of the total, with cumulative investments of about $1 trillion. Priority sectors are finance (30%), manufacturing (25%), and technology (20%). The United States leads through finance and industry; China has lost ground due to EU restrictions.

East Asia

Chinese investment in the region is constrained by competition from Japan and South Korea and by the advanced state of local economies. The main sectors are technology (40%), manufacturing (30%) and renewable energy (15%).

After 2018, US investment in China decreased but increased in Japan and South Korea, largely in high technology. Key sectors are manufacturing (35%), technology (25%) and finance (15%). The United States retains an advantage through its allies; China concedes ground due to competition and a smaller presence in certain high‑tech industries.

Southeast Asia

This region differs from the traditional zones of American capital influence. China substantially increased investment from 2013, peaking in 2018-2020. Southeast Asia became a key region for the Belt and Road Initiative. The main sectors are transport (ports, railways) about 40%; energy (coal, hydropower), 30%; and manufacturing (textiles, electronics), 15%.

US investment also grew from 2013 and accelerated after 2018 due to supply‑chain diversification. Priority sectors are manufacturing (electronics, textiles), 40%; technology (semiconductors, IT), 25%; and finance, 20%.

Overall, China leads in the region through BRI infrastructure projects, while the United States strengthens its position via manufacturing and technology, offering an alternative to Chinese influence.

South Asia

Chinese investment in the region is concentrated in Pakistan, providing access to the Indian Ocean. About 50% of investments go to transport infrastructure (ports, roads), 30% to energy (coal, hydropower), and 10% to metal extraction.

The United States mainly invests in India, and investment volumes have grown steadily since 2013 and rose sharply after 2017. Approximately 40% is directed to technology (software, IT), 25% to manufacturing (pharmaceuticals, automobiles), and 20% to finance (venture capital, banking).

Thus, the United States leads China in the region owing to its technology focus in India, while China emphasizes infrastructure in Pakistan.

Central Asia

A key region for the Belt and Road Initiative, due to proximity, China actively invests in energy (gas, oil) about 45%; transport (railways, highways, pipelines) 30%; and resource extraction (metals) 15%.

American investments are modest here due to competition with China and Russia; they concentrate in energy (40%), resource extraction (30%), and manufacturing (15%). China, therefore, dominates through strategic investments in energy and transport, while the United States maintains a minimal presence.

The Middle East

Chinese investments have grown steadily since 2015, driven by the Belt and Road Initiative and energy projects. The main sectors are energy (oil, gas), 50%; transport (ports, logistics), 25%; and resource extraction (metals), 15%.

US investments rose from 2013 and peaked in 2017-2019, then slowed because of political instability. Principal sectors are energy (40%), finance (25%), and technology (15%).

Overall, China leads the United States through large energy projects and BRI activity, while the United States focuses on allies and lags in total investment scale.

Australia and Oceania

Chinese investments peaked in 2013-2016 and then declined due to Australian restrictions. Still, 95% of Chinese investment in the region goes to Australia. The main sectors are resource extraction (iron, coal, etc.), 40%; energy (coal, gas), 25%; and agriculture (land, food production), 20%.

US investments are also concentrated in Australia and have grown steadily since 2013. Key sectors are energy (gas, coal) 30%; resource extraction (iron, gold, etc.) 30%; and finance (banks, funds) 20%.

The United States and China are at parity in investment in the region.

Latin America

China invested actively in the region in 2013-2019, but rates slowed due to economic and political instability. The main sectors are energy (oil, hydroelectric) 40%; resource extraction (copper, lithium) 30%; and agriculture (soybeans, land) 15%.

US investments are concentrated in offshore financial centers (about 50%) and in the region’s largest economies (Brazil, Chile). Key sectors are finance 40%, energy 25%, and manufacturing - 20%.

In this region, the United States leads through the financial sector, while China focuses on raw materials and lags in finance.

Africa

Chinese investment is concentrated in resources and infrastructure – the region also remains an important destination for Chinese loans and construction contracts. Main sectors are energy (oil, renewables) 40%; resource extraction (copper, cobalt) 30%; and transport 15%.

US investment has grown slowly and remains modest. Principal sectors are technology (IT, telecommunications) 35%; energy 25%; and resource extraction (gold, diamonds, etc.) 20%.

In Africa, China substantially outpaces the United States in resource investment, while the United States is limited to niche projects and a smaller strategic presence.

This is the map of investment confrontation between the United States and China across world regions. It may appear that Chinese capital does not pose a strong threat to the United States: Chinese investment exceeds American investment in only four of the ten regions considered. Nevertheless, this constitutes a significant threat to American capital, because there is no other economic power in the world capable of competing with the United States at this scale. Moreover, if the trend continues, China could, in the coming decades, not only consolidate its leadership in these regions but also increase investment in other regions, displacing the United States.

Under intensified global economic rivalry, the confrontation between China and the United States has reached a stage at which Chinese capital and goods are instruments that undermine the traditional dominance of the American economy.

Key facts illustrating this process:

- Chinese goods undermine the position of American capital in consumer markets by displacing US products through low prices and mass production that reduces revenues of American firms and employment in the United States.

- Chinese exports increase the United States’ economic vulnerability by eroding its domestic manufacturing base.

- Chinese capital, by investing in technology, weakens American leadership. It creates competition in key high‑technology sectors and reduces the world’s reliance on American innovations.

- Chinese capital, through politico‑economic projects (for example, the Belt and Road Initiative) and rising foreign direct investment in other countries, erodes US influence, drawing countries and resources under Chinese sway.

US Policy: Partnership with the EU and Strained Relations with China

Relations between the United States, the European Union, and China display two poles: a partnership with Europe and a growing confrontation with Beijing. At first glance, this difference may seem odd: the EU, possessing considerable economic power, could theoretically compete with the United States in the same way as China yet this has not been the case. At least, it has not been so far.

The conventional view that the US-EU alliance rests on shared “democratic values,” while confrontation with China stems from its “authoritarianism,” is superficial and does not reflect the deeper causes of these relationships. Ideological slogans such as “defending democracy” or “combating authoritarianism” serve primarily as a cover for protecting the economic interests of capital.

The alliance between the United States and the EU is founded on the alignment of economic interests among their ruling circles, which represent transnational corporations and financial institutions. Their interests converge because of the deep economic and political interdependence that began with the Marshall Plan.

The Marshall Plan created conditions for a long‑term “alliance” by linking American capital with European markets and production. From 1948 to 1952, the United States provided $13 billion (about $150 billion in 2023 prices) to restore the economy of Western Europe after World War II. Sixteen countries received aid, including West Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. The plan’s main objectives were to rebuild industry, prevent economic collapse, and, crucially, to contain the spread of communism.

Large‑scale financial support for European industry attracted many American corporations to Europe. By 1950, US foreign direct investment in Europe reached $1.7 billion in contemporary prices, which significantly advanced the expansion of American capital in the region.

The Marshall Plan was not only an economic measure but also a political project. During the Cold War, it shaped Western Europe as an anti‑communist bloc under US influence. In 1949, this position was institutionalized with the creation of NATO, serving the common aim of European and American capital to protect the capitalist world order from the threat of a global socialist revolution.

Moreover, the EU itself emerged in part thanks to the Marshall Plan and US support. In 1948, the Organisation for European Economic Co‑operation (OEEC) was founded to coordinate the distribution of aid. This was a first step toward European integration that eventually led to the formation of the EU.

In the twenty‑first century, European and American capital are deeply interwoven through mutual investment. From 2000 to 2023, cumulative US direct investment in the EU amounted to $3.95 trillion, while EU investment in the United States totaled $3.46 trillion (64% of total FDI in the United States). Together, the United States and the EU account for roughly 40% of world GDP and a substantial share of global trade. Their alliance enables them to shape the rules of the global economy through international institutions.

European capital, therefore, is an ally of the United States, integrated with American capital, supporting its leadership and sharing the objective of preserving the dominance of Euro‑American capital while maintaining US primacy. Chinese capital, by contrast, threatens the United States: it displaces US products, undermines manufacturing, competes in technology, and draws global resources toward itself. China challenges the US‑centerd model of the contemporary capitalist system and seeks to claim the position of global imperialist hegemon in place of the United States.

II. Lines of Confrontation

2.1. Economic struggle

Since the mid‑2010s, China’s rise as an alternative center of capital accumulation has begun to threaten the United States’ dominant position. Naturally, once China’s ambitions became apparent, American capital sought to isolate it from international markets and advanced Western technologies in order to limit the growth of the Chinese economy. This produced trade wars and economic confrontation between the two countries.

Blocking Chinese investment

Before the trade wars began, a mechanism for screening investments was introduced in the United States to block the growth of Chinese influence in strategic sectors.

Since 2018, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) has tightened control over Chinese investments following the adoption of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA). Previously, more than half of the investment in the US technology sector originated from China. As a result, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the United States in 2019 fell by more than five times compared with 2017 and remained at low levels in subsequent years.

Although investment screening helped the United States reduce the role of Chinese investment in the American economy, it also forced China to redirect its investments to Latin American countries, which further strengthened its position in that region.

The United States exerts pressure on its allies to counter China. For example, following US accusations that Huawei engaged in espionage, the British government in 2020 banned the use of the company’s equipment in 5G networks and required operators to remove it by 2027.

Before 2020, Huawei played a significant role in the United Kingdom, having invested £3.3 billion in the economy and supported 26,000 jobs. The decision cost the United Kingdom £2 billion to re‑equip networks. China responded by reducing investment in British projects and redirecting funds to other countries.

Trade War 2018-2024

Trade wars became one of the principal instruments used by the United States in its economic confrontation with China, aimed at reducing the trade deficit and weakening Chinese exports. The first Trump administration initiated this policy, imposing 25% tariffs in 2018 on $50 billion of Chinese goods. By the end of 2019, tariffs covered imports worth more than $550 billion, roughly two thirds of all Chinese exports to the United States. China responded with reciprocal measures, imposing 10% tariffs in 2019 on $75 billion of American goods.

After the change of administration in the White House with Trump’s departure and Biden’s arrival, the intensity of the confrontation did not decline. On the contrary, in 2024, the Biden administration sharply raised tariffs on key Chinese goods: electric vehicles from 25% to 100%; steel and aluminium from 7.5% to 25%; and semiconductors from 25% to 50%. China responded by imposing export restrictions on gallium (used in semiconductor manufacture) and germanium (used in fiber optics, solar panels, and infrared optics).

Under US pressure, the European Union in 2024 imposed 45% tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, accusing China of unfairly subsidising its industry. In response, Beijing urged automakers such as BYD and SAIC to reduce investments in countries that supported these measures.

The trade wars immediately produced significant changes in global supply chains, fragmenting them and redistributing trade flows.

Companies reliant on Chinese production began relocating factories to countries with lower tariffs, Vietnam and Mexico, for example. As a result, Vietnam’s exports to the United States rose from $49 billion in 2018 to $118 billion in 2023. Part of this growth reflects electronics manufacturers, such as Foxconn, moving operations there from China.

China, for its part, increased trade with Africa and Latin America. However, this restructuring raised costs: relocation increased companies’ expenses by 10–12%. For the global economy, this meant higher prices and reduced supply‑chain efficiency, which hit developing countries dependent on exports particularly hard.

A 2019 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that American consumers bore 93% of the tariff burden through higher prices. Total consumer losses amounted to $1.5 billion per month. The effects for China were also tangible: US tariffs reduced Chinese exports by $100 billion per year, contributing to a 1.5% decline in GDP.

The onset of the US-China trade war struck at the model of “globalism” not only as the economic integration of the modern capitalist world but also as a propagandistic ideology. From the idea of “free movement of capital and goods,” under which capitalist countries supposedly “cooperate peacefully,” the world moved closer to a bloc confrontation among imperialist centres – a classic condition of international relations under capitalism.

This period of trade wars also coincided with the introduction of the CHIPS Act – another significant US step against China intended to restrict China’s access to advanced semiconductors and to restore US leadership in the sector. Enacted in 2022, the law provided $52 billion in subsidies for chip production in the United States, including $40 billion for a TSMC plant in Arizona, and was accompanied by sanctions banning exports of advanced technologies to China.

Semiconductors, or chips, are the foundation of the modern economy. They power smartphones, computers, automobiles, medical equipment, telecommunications systems, military technologies, and artificial intelligence. They underpin cloud computing, the Internet of Things, autonomous transport, and household appliances. We have previously written about the Chip trade war.

Historically, the United States led chip design through companies such as Intel, NVIDIA, AMD, Qualcomm, and Apple, which develop processor architectures, graphics chips, and design software. Major chip manufacturing is concentrated in Taiwan. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is the global leader, having mastered the production of advanced 2 nm chips.

The United States depends on Asian supplies of so‑called “mature” (or old) chips (process nodes of 28 nm and above), a substantial share of which are produced in China. Despite limited access to advanced technologies because of US sanctions, China has actively expanded production of mature chips. As of 2023, it accounted for 27% of global manufacturing capacity in the 20-45 nm range and 30% in the 50-180 nm segment. These semiconductors are widely used in the automotive industry, electronics, industrial and medical equipment, and telecommunications.

Mature chips form the basis of many devices, underscoring their strategic importance for the world economy. Drawing on extensive experience in key technologies, China pursues a strategy of flooding the market with lower‑cost products to displace global competitors. This tactic has already proven effective in sectors such as solar energy and battery manufacturing.

Widespread use of Chinese chips can leave national economies vulnerable in the event of a confrontation with China. Dependence on Chinese supplies could produce critical shortages at key moments, enabling China to subordinate other states to its interests.

Thus, despite lagging in advanced chip manufacturing, China is well positioned to capture the market for mature semiconductors, where it has already made significant gains. The CHIPS Act, adopted by the United States, aims to contain China’s progress in advanced technologies, but does not resolve the problem of China’s dominance in the mature‑chip segment.

Escalation of the Trade War in 2025

In 2025, the trade war between the United States and China, intensified with the return of D. Trump to power, reached a qualitatively new level in the struggle for global economic dominance. The main trend is an intensified economic confrontation, with the United States seeking to undermine China’s position by using trade tariffs as a principal instrument.

China produces far more goods than its domestic market can absorb and is therefore highly dependent on exports, a vulnerability the United States is pressing. Over a matter of weeks from late March to early April, the economic confrontation between China and the United States rapidly escalated: the sides exchanged a series of new tariffs on each other’s imports. The United States began raising tariffs in March, progressively increasing the overall rate on imports of Chinese goods to 145% by April.

The purpose of the American tariffs is to reduce the presence of Chinese goods on the world market and to prevent their dominance, especially in strategic sectors such as technology and engineering. American capital reasonably fears that Chinese products may eventually displace American ones. An experience of this kind already exists.

A similar scenario occurred in the 1980s, when the Japanese automobile industry, supported by American investment and technology, rapidly captured the global market. Japanese companies such as Toyota and Honda offered higher‑quality and more affordable cars, causing a sharp drop in demand for products from American giants General Motors and Ford. By the early 1990s, the market share of American manufacturers in the United States had declined, and many plants closed, producing unemployment and economic decline in Detroit and other industrial centres.

That painful experience compels the United States to act decisively to prevent a far greater threat from China. While Japan in the 1980s challenged American corporations mainly in automobiles and high‑technology goods, the People’s Republic of China now poses an existential threat to the United States, endangering its economic and political dominance worldwide. This struggle unfolds against the backdrop of a deepening crisis of the global capitalist system, intensifying inter‑imperialist contradictions and the prospect of new global conflicts.

The tactical approach of the American administration in this new phase of the tariff war is clear. On the one hand, the United States closes its market to Chinese goods. On the other hand, it exerts pressure on other countries through the same tariff mechanism, forcing them to make concessions. In effect, the American administration poses a stark choice to countries worldwide to either comply with its demands or lose profit. This is straightforward, undisguised coercion, expressed in massive tariffs and unilateral revisions of trade and economic agreements.

These two directions combine to form the current US tariff policy. Ultimately, it is aimed at achieving three key objectives for the United States:

- Weakening China through economic pressure and attempts to induce a crisis of overproduction by cutting China off from markets;

- Pressuring allied and “undecided” countries in order to prevent closer ties with China and to tighten American influence within spheres already under US control;

- Reindustrialisation and an increase in the military budget through the return of industrial capacity to the United States, an established plank of Trump’s campaign platform.

As noted in our piece on the US elections, the administration of Donald Trump represents the radical wing of the American oligarchy. This segment of the ruling class seeks to restore the United States’ former position through an extremely aggressive policy and a tariff war with China, one of its most significant instruments.

At the same time, the tariffs introduced not only against China but also against other countries make exporting to the United States unprofitable. Whatever the outcome of Trump’s “tariff negotiations” with other major world economies, it is evident that the trade war he has unleashed will lead to a radical reorganisation of manufacturers’ logistics worldwide. The consequences will spread through the entire global production chain, produce shocks at all levels of the world economy, and intensify inter‑imperialist contradictions to an extreme degree. Ultimately, the now‑open confrontation between the United States and China is nothing other than a path toward a new world war – a risk made more likely by China’s reciprocal measures.

Thus, China, which had previously avoided sharp confrontation to preserve access to the American market (for example, by limiting cooperation with Russia and observing secondary sanctions), has adopted similarly aggressive policies. Beijing raised tariffs on American goods to 125%, imposed export restrictions on rare earth elements (China accounts for 60% of global production and 85% of processing), placed American companies PVH Corp and Illumina on its “List of Unreliable Entities,” and opened an antitrust investigation against Google.

In doing so, China sent two messages to the world: a willingness to negotiate and peacefully delineate spheres of influence, and a determination to resist further escalation by the United States, including by imposing direct measures such as sanctions against American companies.

In an effort to strengthen domestic production and redistribute profits, the United States imposed tariffs on imports from most countries. Initially, this step created a potential opportunity for China to form an anti‑American economic bloc by uniting states harmed by US protectionism.

Following a dialogue between Xi Jinping and António Costa in January, during which countermeasures to protectionism were discussed, China and the EU began talks. In March and April, China’s Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao and European Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič agreed to study replacing 45% tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles with minimum pricing measures. In July 2025, the President of the European Council, António Costa, and the European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen, planned to visit Beijing for a summit with Xi Jinping. This decision clearly reflected the EU’s desire to maintain dialogue with China amid tensions with the United States.

The situation then changed rapidly. Apparently recognizing the risk of an anti‑American bloc forming, Trump announced a 90‑day pause in the application of elevated tariffs, leaving a base rate of 10% for most countries except China.

As a result, China lost the initial advantage it might have gained from other states’ dissatisfaction with American tariffs. Even countries traditionally within China’s economic influence, such as Vietnam and Cambodia, chose a pragmatic course of negotiating with the United States rather than joining an anti‑American front. These moves by close partners compelled China to intensify diplomatic efforts to retain influence in the region: in April, Xi Jinping visited Vietnam, followed by trips to Malaysia and Cambodia.

Confronted with a relative balance in which neither side could obtain a decisive advantage, the United States and China in May agreed to reduce tariffs for 90 days: Washington lowered tariffs from 145% to 30%, and Beijing reduced them from 125% to 10% upon resuming exports of rare earth elements. In effect, the parties temporarily froze the conflict and took a pause. It is most likely that in the near future, after replenishing and strengthening their capacities and expanding their alliances, China and the United States will enter a new phase of escalation, since the causes of the confrontation remain.

Regardless of how the trade war develops, it is clear that the rivalry between China and the United States has entered a more active economic phase. Through tariff barriers, trade restrictions, and economic pressure, both countries will seek to expand their spheres of influence while weakening the other’s position.

2.2. Political and Diplomatic Struggle

The political rivalry between the United States and China has intensified as a natural extension of the economic conflict between the two countries. This rivalry encompasses key regions and countries where the interests of the world's two largest economies intersect. The tariff war and economic rivalry only exacerbate this political confrontation.

Taiwan

Taiwan is one of the central points of political struggle between the United States and China. China considers Taiwan an integral part of its territory under the "one country, two systems" principle and attempts to persuade other states to recognize this fact. In contrast, the US supports Taiwan by providing military and diplomatic assistance, though it does not formally recognize its independence.

Both the US and China need Taiwan primarily as a technological and manufacturing base for the semiconductor industry. At the end of the fourth quarter of 2024, Taiwanese companies TSMC and UMC produced 72% of the world's semiconductors.

Amid China's limited access to Western semiconductor technologies, the interest of both countries in Taiwan continues to grow. China is in a difficult position because it considers Taiwan, the world's chip manufacturing hub, to be part of its territory, yet its own semiconductor technologies lag behind, accounting for less than 10% of the global market.

Thus, three important factors come into play:

- China has a formal reason for seizing Taiwan: it considers Taiwan to be its territory. This claim is formally recognized by most countries in the world.

- Controlling Taiwanese semiconductor production would allow China to quickly develop its industry and become a world leader in technology.

- Taking Taiwan would also give China the opportunity to cut the United States off from the largest semiconductor technology base.

The U.S. is aware of this threat, which is why it supports Taiwan through visits by high-ranking officials, arms supplies, and rhetoric about defending "democracy." These actions provoke protests in China, which considers them interference in its internal affairs.

One of the most high-profile events in this standoff was the visit of U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan in 2022. In response, China conducted unprecedented military exercises around the island, including live-fire missile drills and a simulated blockade. It was the largest display of force by the PRC in decades.

In accordance with the National Defense Authorization Act, the United States increased its military aid to Taiwan to $10 billion in 2023.

In May 2024, following the inauguration of Taiwan's new president, Lai Chingte, who is regarded as a supporter of independence, China initiated the "Joint Sword 2024A" exercises. These exercises were designed to "punish separatists" and caution "external forces" (i.e., the U.S.). The exercises included a simulation of a blockade of the island's key ports.

In October 2024, China held another large-scale military exercise focused on blockading Taiwan and controlling strategic areas.

Indo-Pacific region

The U.S. IndoPacific Strategy (IPS) is a foreign policy initiative aimed at strengthening the United States' position in the IndoPacific region. This region covers territories from the west coast of the United States to the Indian Ocean and includes Northeast and Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Oceania. The region is considered crucial to 21st century global economics and politics, as it is home to over half of the world's population and accounts for approximately 60% of global GDP and twothirds of global economic growth.

The concept of the Indo-Pacific region as a unified strategic domain began to take shape in the United States during the 2010s, particularly during the Trump administration. In 2018, the U.S. Pacific Command was renamed the U.S. IndoPacific Command (USINDOPACOM), a symbolic step that underscores the region's new militarization trend.

In 2019, the Trump administration released the Indo-Pacific Strategy Report. In the report, China was labeled a "revisionist power" that seeks regional hegemony and global dominance in the long term.

The strategy has been further developed under the Biden administration. In February 2022, the White House published an updated version of the strategy, emphasizing cooperation with allies to create a "free and open" region. The U.S. has continued to strengthen alliances, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad: U.S., Japan, Australia, and India) and AUKUS (Australia, the U.K., and the U.S.), and has launched the IndoPacific Economic Framework (IPEF) to promote economic cooperation.

The U.S. maintains a significant military presence in the region, with approximately 375,000 military personnel and civilian staff under the command of USINDOPACOM. The U.S. also conducts exercises with Japan and South Korea, such as Freedom Edge, and is building up the defense capabilities of its allies.

In May 2022, Chinese leaders, including Foreign Minister Wang Yi, repeatedly claimed that the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy aimed to “create divisions, incite confrontation, and undermine peace.” Wang Yi called the strategy “doomed to failure,” arguing that it runs counter to the region's interests. In March 2023, China accused the U.S. of trying to "encircle China" with this strategy.

China believes that the IPS is promoting the narrative of the "Chinese threat," portraying the PRC as an aggressor in order to justify the strengthening of the U.S. presence in the region. In response, China is promoting its Belt and Road Initiative to increase its economic and political influence in Asia and beyond. Through the BRI and trade, China is making countries dependent on its capital and markets. This reduces their interest in the IPEF, which does not yet offer comparable investments.

China is expanding its cooperation with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), offering alternative economic partnerships such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which was signed in 2020. The RCEP is an initiative aimed at strengthening economic cooperation and creating the world's largest free trade area, covering approximately 30% of the global GDP.

China avoids direct confrontation with alliances such as the Quad and instead works with individual countries, offering them favorable terms. This could lead to a split among U.S. allies because not everyone in the region is willing to fully oppose China. For instance, India continues to maintain economic ties with China despite growing contradictions between the two countries.

Despite the significant U.S. military presence in the region, China maintains its dominant position thanks to its economic influence through the Belt and Road Initiative and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The U.S. lags significantly behind in economic competition because its IPEF does not offer comparable investments.

South China Sea

Since 2013, China has reclaimed approximately 1,300 hectares of land in the South China Sea, turning the reefs and shoals of the Spratly Islands into fortified military bases. For instance, China has constructed military facilities on Mischief Reef, including a 3-kilometer runway capable of accommodating strategic bombers and port facilities for military ships. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), the islands are equipped with HQ9 anti-aircraft missile systems, which have a range of up to 200 kilometers, and YJ12B anti-ship missiles. This strengthens China's military control over the region.

China claims 90% of the South China Sea based on the so-called “nine-dash line,” despite the fact that a 2016 ruling by the Hague Tribunal found these claims to be legally unfounded. Every year, about $3.4 trillion of global trade, including 80% of China's energy imports, passes through this region, making it extremely important for the Chinese economy.

In turn, the US and its allies are increasing their military presence and exerting diplomatic pressure on China. Since 2015, the U.S. Navy has conducted over 100 freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs), deploying destroyers and aircraft carriers within 12 miles of the disputed islands. China has repeatedly viewed this as a provocation.

The militarization of the South China Sea has exacerbated tensions between China and its neighboring countries, particularly the Philippines, a U.S. ally. Clashes between Chinese and Philippine vessels became more frequent in 2023, including incidents involving the blocking of Philippine fishermen and clashes at Scarborough Reef and Second Thomas Shoal. These actions reflect China's attempts to strengthen its control over disputed territories. Backed by military infrastructure on artificial islands, these actions increase pressure on regional players and provoke a response from the U.S.

Vietnam has also reported an increase in violations. In 2022 alone, Chinese ships entered their exclusive economic zone near the Paracel Islands over 40 times.

Although Japan has no direct claims in the South China Sea, it is nevertheless stepping up its support for its allies. For example, in 2022, Japan transferred ten ships to the Philippines. Japan also participates in Quad exercises. In 2024, Japan conducted joint maneuvers with the United States, Australia, and India near the disputed waters.

Diplomatic negotiations, such as the efforts of ASEAN and China to establish a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea, have stalled. In 22 years, an official compromise has yet to be reached due to disagreements over the scope of application and dispute resolution mechanisms.

At the 2023 ASEAN summit, China accused the US of "incitement," to which the US responded by pointing to the PRC's "aggressive expansion." These accusations only exacerbated the situation, leaving the region in a fragile state of equilibrium where any incident, from a ship collision to an aircraft interception, could escalate into a major crisis.

Nevertheless, with the exception of direct U.S. allies such as the Philippines, countries in the region are increasingly focusing on economic ties with China, making the region an "asset" for the PRC.

Iran

Trade relations between China and Iran began in the 1970s but became significant following the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Iran was subjected to sanctions, and China provided military assistance during the Iran-Iraq War. Since the 2000s, China has become Iran's "window to the world," particularly after the U.S. tightened sanctions in 2018. In turn, Iran has acted as a pro-China force in the region, distracting the U.S. from the Indo-Pacific region and weakening its influence in the Middle East.

In 2021, Iran and China signed a 25-year strategic partnership agreement. In exchange for oil supplies to China at reduced prices, China agreed to invest $400 billion in Iran's oil and gas sector and petrochemical industry. Despite US sanctions, China became the largest buyer of Iranian oil by 2024, importing about 1.2 million barrels per day.

China uses a “shadow fleet” of tankers registered in third countries and complex financial schemes to circumvent sanctions. These schemes include payments through small banks and cryptocurrencies. In 2022, the U.S. imposed secondary sanctions on several Chinese companies accused of buying Iranian oil under the guise of Malaysian or Indonesian oil.