What is a Communist Party and what are its tasks? On what principles is it created and what mistakes are encountered along this way? Answering such questions in this material, we elaborate the Leninist approach to the creation of a political party.

Background

During the period of the development of the first Russian revolution 1905-1907, heated debate was waged on the question of the party within the Russian Social Democratic movement. On one side of the barricades were figures such as Martov, Dan, Axelrod and those others who stubbornly adhered to the social democratic traditions of the past. Guided by the large Western European parties of the Second International, they believed that it was precisely by following their principles that the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP) would guarantee the success of the approaching revolution.

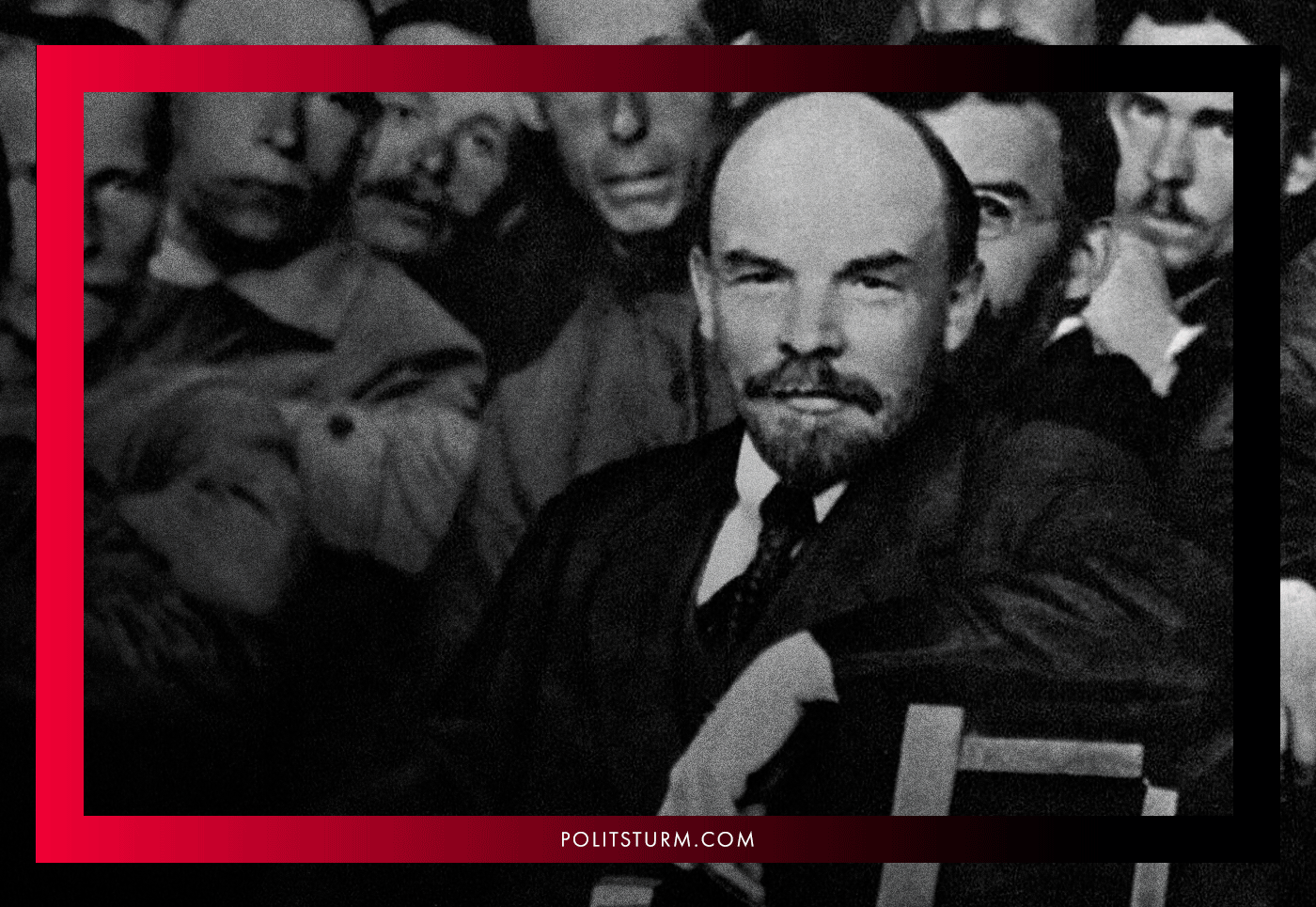

Opposing this position was a group led by Lenin, categorically dismissing the “classical” social-democratic type of organization. This faction argued that for the success of the revolutionary struggle, Russia would need a new type of party – the revolutionary party of the proletariat. It was the development of this thesis to which Lenin devoted two major works of that period: “What Is To Be Done?” and “One Step Forward, Two Steps Back”, which formed the basis of a new party organization.

In political history, this ideological confrontation was reflected in the divergence of two antithetical factions within the RSDLP – the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks. Further drifting from each other, it finally took form in 1912 and turned the groups into independent parties.

Why did this seemingly insignificant organizational issue become such a sharply contested issue? Why did Lenin and the Bolsheviks insist on a split with the Social Democratic heritage, of which Marxism had previously been a part?

The point is that so-called Social Democracy has historically been disunited. Even in the lifetime of Marx and Engels, the international labor movement, represented by the First International, did not just reflect the interests of workers. Even then, within an emerging Social Democracy, petty-bourgeois and bourgeois trends prevailed: Bakunism, Lassalleans, Proudhonism, Fabianism, etc. Marx and Engels waged a tireless struggle against these anti-proletarian deviations, which ended with the collapse of the First International, largely due to the subversive activities of the anarchists.

After the establishment of the Second International in 1889, a renewed struggle flared up between Marxism and the clearly anti-proletarian tendencies: thus, by 1893, anarchists of various stripes were forced to leave this international organization. One by one, non-Marxist interpretations of socialism were broken down.

Let us note that in the first years of its existence, the Second International ultimately stood on a revolutionary (Marxist) point of view. For the most part, this was the result of the titanic endeavors of Friedrich Engels, who made big efforts to ensure that Marxism became a guiding star for the social democratic parties of that period.

However, after the death of Engels in 1895, the Second International gradually began to slide into reformism and adaptation to the capitalist order.

The reason for this was that Social Democracy, as it was, remained a loose bloc of proletarian and non-proletarian elements, and the latter, after the triumphant victory of Marxism over other socialist theories, masked their essential character with a Marxist disguise.

The need arose for a decisive disengagement from the old Social Democracy, which perfectly suited the proletariat at a certain stage of political development – the stage of accumulation of forces – but was completely useless and even harmful in the approaching era of proletarian revolutions.

Delimitation was not to be declarative, but of the most principled character. It was necessary to discard false social-democratic hopes for reforms and the gradual, moral evolution of capitalism into socialism, even the absolute foundations of social democracy: its organizational type and its construction of party work.

This was necessary because the organizations of the old Social Democracy were exclusively focused on parliamentary, bourgeois-democratic, legal activities. They did not even account for the very possibility of active participation of the entire party in the revolutionary process, the seizure of political power by the party in a direct confrontation with the bourgeoisie, or the leadership of the party by the revolutionary masses.

Furthermore, Social Democracy was fundamentally divided. The old Social Democracy was a bloc of groups which expressed the varying interests of the proletariat and the petty and middle bourgeoisie. There could be no talk of any unity of action within the framework of the development of the revolutionary process simply because the groups that made up the Social Democratic parties had different class goals and intended to achieve them in different ways.

Lenin, foreseeing the onset of the proletarian revolutions epoch, demanded the creation of a party pursuing the goal of exclusively one class – the proletariat. The only class that was capable of conquering power and incite a real transformation of society on the basis of the doctrine of scientific socialism. It was to these goals that the structure, organizational type and personnel composition of a new type of party, the revolutionary party of the proletariat, had to correspond.

Later, after the creation of the Third International, the Bolsheviks pursued a line of transformation (“Bolshevization”) of those political groups already existing in the world (mainly as the left-wing of social democracy) and the creation of truly revolutionary parties. New parties, whose essence was not loud slogans and appeals, but loyalty to the theoretical and practical course of Leninism.

Lenin’s views on the party

Is it correct to say that Lenin simply invented his own organizational type, which we, as it may seem, are trying to present as a universal means of solving all problems, suitable for all times? No.

Leninism is the unity of the theory and practice of the proletarian revolution. This means that any position of Leninism is not a figment of the imagination of any person, even a very wise person, something suitable for the beginning and middle of the 20th century, but now completely irrelevant.

Leninism and, in particular, the Lenin’s type of a party of this new type, is a reflection in practice of the principles of the ideology of the proletarian revolution. As long as the proletariat is called to put an end to the economic system of oppression, Leninism will remain the only doctrine capable of providing this class with the practical tools for carrying out its historical mission.

No other political-organizational type, no matter how subjectively attractive it may be, is able to accomplish this transformational mission, simply because of their non-proletarian class basis. And if we agree that only the proletariat is capable of destroying capitalism, that only proletarian ideology is really capable of undermining bourgeois hegemony in society, we must admit that only Leninism, and not any petty-bourgeois or bourgeois organizational concepts, will act as a practical method of achieving the proletariat’s set goals.

Considering all that’s been said here so far, we are surprised by the brazenness of all the revisionists and opportunists today who proclaim themselves to be “adherents of Marxism-Leninism”. This impudence is explained by the regrettable ignorance of those people who sincerely wish to fight for socialism and fall for “pale-pink” demagogues hiding behind a red flag.

It must be understood that Marxism-Leninism (Communism) is inseparable from the Leninist type of a party: it is one whole. To acknowledge Marxism-Leninism in words, but at the same time to deny the Leninist scheme in whole or in part, to screw in elements of anarchism, liberalism or bourgeois democracy, to try to cover up the question of organization with detached reasoning, to abandon the practical part of the theory under various pretexts, is to deny Marxism-Leninism. No one has the right to call himself a Marxist-Leninist or a Communist while rejecting the practical principles of Leninism.

In order for the reader to understand who is really setting (at least in the long term) the goal of transforming society on socialist principles, and who is just earning money and defrauding crowds of suffering people for the amusement of the bourgeoisie, we must consider the main features characterizing the Lenin’s new type of party.

Discipline

Class-consciousness is one of the main requirements for a member of a revolutionary party. It is not a question of party members knowing by heart the 55 volumes of Lenin’s works, or being able to parse in detail and prove each point of the program. That would be impossible.

To understand these tasks and methods of solving them, to understand the essence of socio-political phenomena and the role of the party of the working class, to continuously raise the level of theoretical and practical knowledge – thereby increasing the effectiveness of our own actions and those of the general party – that is what we mean by consciousness and ideological thinking.

It is from consciousness that the strictest discipline of the new party develops. Here it is not implanted mechanically, not by force, but from everyone’s realization of the necessity for the party to fulfill the role that history has assigned to it.

A party is not a club or a community of enjoyers of politics. The party is the vanguard of a class; the class army of the proletariat which sets itself toward the grand task of transforming the world and society. Without discipline, this class army cannot exist and cannot fulfill its tasks either in peacetime or in wartime.

“I repeat: the experience of the victorious dictatorship of the proletariat in Russia has clearly shown even to those who are incapable of thinking or have had no occasion to give thought to the matter that absolute centralization and rigorous discipline of the proletariat are an essential condition of victory over the bourgeoisie” – Vladimir Lenin, “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder”.

Discipline is the exact and unconditional fulfilment by all Party members and Party organizations of all orders of the leading bodies, regardless of whether individual cadres believe this decision is right or wrong, or whether they agree with this decision or not. Once the party has made this or that decision, it is the duty of the party activist to do it.

Failure to comply with the decision is considered as a serious violation of the foundations of the Bolshevik party system and is punished with all severity. And if in moments of revolutionary recession such punishment could be expulsion from the ranks of the party, then in periods of upsurge – armed struggle or civil war – such, even less serious violations, were punished extremely harshly.

Why is strict discipline needed?

It is needed in order to achieve success.

The party acts as a single entity, as a single mechanism, and not as a conglomerate of individuals, each of whom has its own view on a particular issue. The party must be sure that each of its members will do what the leading core obliges them to do, even if they do not agree with any decision. Thus, each party member subordinates his personal will to the will of the collective, of the majority, and do it voluntarily.

No one can be forced to join the party or be in its ranks. By joining a party, a person voluntarily assumes the responsibility to fulfill all of its decrees without receiving any personal privileges in return. There is no personal reward, which – to contrast – is inherent in bourgeois parties.

This does not mean that the party rejects the possibility of discussing this or that issue, that the “party dictatorship” dominates the individual and doesn’t recognize any rights of one person. On the contrary, the party is ready to discuss various issues, submitting – depending on their severity, – these issues for the broad public discussion, but after the decision has been made, it must be implemented. It is easy to complete the tasks that one fully agrees with. But true discipline manifests itself where you have to submit to a decision with which you disagree.

It is exactly with this iron discipline that the party of the new type differs from the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois (including social democratic) parties, who are divided into many groupings and bury any initiative under endless, meaningless discourse, in the end acting apathetically and without initiative.

Discipline also protects the party from the ideological influence of non-proletarian classes trying to intrude the unstable ranks of the proletariat, ranks which fluctuate most strongly in moments of crisis. It is then that discipline, endurance and sober analysis save the party from alarmism, depressive moods and surrender; sentiments which are inevitably spread in party circles by wavering members.

Under external pressure, only iron discipline and strict centralization protect the party of the working class from being influenced not to move to alien positions, to be moved to positions of petty-bourgeois adventurism or right-wing revisionism which bring about its defeat. This is true both under the conditions of the struggle for power and the construction of socialism when the party is being pressed upon not only by the foreign bourgeoisie but also by the remnants of the non-proletarian classes within the country.

The petty bourgeoisie, under the bourgeois intellectuals’ influence, and the lumpen-proletarian strata both despise discipline, which they will say suppresses “private initiative”. These subjects withhold nothing to discredit the very concept of party discipline, ridicule it and smear it as something servile and alien to the magical world of socialism that they dream of.

But the rejection of discipline – no matter what kind of “revolutionary” sauce it’s slathered with, – is the rejection of the foundations of Bolshevik party building: this is a struggle against the socialist revolution.

The stronger the discipline, the stronger the party, and the more dangerous it is for capitalism.

Through its “agents of influence”, infected with individualism, the bourgeoisie seeks to undermine the meaning of discipline in general, muttering about “mechanical subordination” or “disciplinary formalism”, about the harm of “blind execution”, about the “barracks-typed” organization where everyone is forbidden to talk, and finally about the erroneous orders of an unquestionable party leadership, whose robotic implementation turns out to be the most harmful.

Of course, mistakes in tactics are possible and, at a certain stage (due to the lack of the necessary experience and knowledge), are even inevitable. But this is by no means an argument to call for non-compliance with party orders. You can demand from the party to reconsider a decision that seemed to someone to be erroneous, you can demand its discussion, but to refuse to obey the decision on the grounds that it seems “wrong” means destroying organizational ties, means undoing the revolutionary party.

Iron discipline of the vanguard squad of the working class is the only guarantee of a successful conquest and retention of power in the struggle against the world’s most powerful enemy – the capitalists. In their hands, all the levers of political, military, economic and cultural domination are concentrated. To go to battle unprepared with such an adversary, who is ready to do anything to preserve his place in the social system, who has assembled in his corner a mass of media personalities, apathetic dreamers and anarchic sages who despise “slavish” discipline, means dooming us to defeat.

Centralism

Without a single leading center – the “headquarters” of the party, no party unity is possible. To imagine the revolutionary party as a conglomerate of individual organizations cooperating with each other on a voluntary basis runs contrary to the foundations of Bolshevik organization.

Without this arrangement, there can be no subordination of the minority to the majority in the name of the success of the common cause; there can be no talk of any unity of action, of any concentration of forces to make a crushing blow. Petty-bourgeois semi-anarchist federalism leads to laxity and indiscipline, constant squabbles in debate which paralyze revolutionary work, nonsensical and disastrous local initiatives which undermine the workers’ confidence in the revolutionary organization, and to a frivolous attitude towards work.

Bolshevism fundamentally rejects the principle of federalism. The party, as has already been said, is the vanguard of the working class, a disciplined political army facing such colossal tasks that would require unity of action.

The merry band of Makhnovist freeman, the anarchist federation of ebullient enthusiasts who are not bound by any obligations to each other, an honorable confederation of “free people” who have turned their personal “freedom” into a fetish and proudly stand in disagreement on every question they personally dislike: all this is a product of petty-bourgeois individualism elevated to an organizational level.

In his work “One Step Forward, Two Steps Back”, Lenin took special care to eliminate this “lordly-anarchist” approach:

“The discipline and organization which come so hard to the bourgeois intellectual are very easily acquired by the proletariat just because of this factory “schooling”. Mortal fear of this school and utter failure to understand its importance as an organizing factor are characteristic of the ways of thinking which reflect the petty-bourgeois mode of life and which give rise to the species of anarchism that the German Social-Democrats call Edelanarchismus, that is, the anarchism of the “noble” gentleman, or aristocratic anarchism, as I would call it. This aristocratic anarchism is particularly characteristic of the Russian nihilist. He thinks of the Party organization as a monstrous “factory”; he regards the subordination of the part to the whole and of the minority to the majority as “serfdom” (see Axelrod’s articles); division of labour under the direction of a center evokes from him a tragi-comical outcry against transforming people into “cogs and wheels” (to turn editors into contributors being considered a particularly atrocious species of such transformation); mention of the organizational Rules of the Party calls forth a contemptuous grimace and the disdainful remark (intended for the “formalists”) that one could very well dispense with Rules altogether.

<…>

To people accustomed to the loose dressing-gown and slippers of the circle domesticity, formal Rules seem narrow, restrictive, irksome, mean, and bureaucratic, a bond of serfdom and a fetter on the free “process” of the ideological struggle. Aristocratic anarchism cannot understand that formal Rules are needed precisely in order to replace the narrow circle ties by the broad Party tie. It was unnecessary and impossible to give formal shape to the internal ties of a circle or the ties between circles, for these ties rested on personal friendship or on an instinctive “confidence” for which no reason was given. The Party tie cannot and must not rest on either of these; it must be founded on formal, “bureaucratically” worded Rules (bureaucratic from the standpoint of the undisciplined intellectual), strict adherence to which can alone safeguard us from the willfulness and caprices characteristic of the circles, from the circle wrangling that goes by the name of the free “process” of the ideological struggle”.

A leading center guided by the interests of the proletariat and ensuring the unity of action of all party organizations through a “bureaucratic” system of unconditional subordination is the basis for the successful functioning of a revolutionary party.

Bureaucracy here is not an end to itself, a copy of the activities of bourgeois parties.

The bureaucracy of a revolutionary party is an inevitable and objective consequence of the expansion of the struggle, the inclusion of ever-wider sections of the working class in revolutionary activity, when working on the basis of personal relationships and personal trust becomes no longer possible.

Any undertaking capable of undermining this party centralization contradicts Leninism, which refutes the possible existence of several leading centers within the party of the working class. Any such undertaking within the proletarian party, in fact, is a manifestation of an anti-proletarian ideology opposing the party line.

Lenin’s organizational scheme was developed towards eliminating the very likelihood of an emergence of certain internal factionalizations on the basis of which “alternative” anti-proletarian centers of influence could grow in the future.

For example, even in pre-revolutionary times, when it came to joining the young Bolshevik party of certain national-revolutionary Social Democratic groups (Jewish Bund, Adalat, Borotba, Gummet, Hnchakyan, etc.), Lenin pursued a line against “merging”, “union”, and “broad cooperation”, only accepting the full integration of various organizations without maintaining their “original” structure.

This excluded the possibility of the emergence of a kind of “national faction” or “groups of old friends” within the party which would be fenced off from the rest of the party masses, thereby violating the principles of centralism and undermining party work.

Later, during the 10th Congress of the RCP(b) in March 1921, on the basis of the experience of the struggle for the establishment of socialism, a resolution was adopted at the suggestion of Lenin “On Party Unity” which categorically condemned and prohibited any attempts to create separate groups or factions. These undermine party unity, contributing to the penetration of hostile elements and sentiments into the party ranks, and weakening the revolutionary party.

Party democracy

At the same time, the centralism of the party structure and iron discipline do not at all mean that the Leninist party functions exclusively on the blind subordination of the activists to the dictatorship of party leaders.

On the contrary, a broad discussion of specific questions of theory, of this or that party event, is key to the successful functioning of the party as a revolutionary force. The broader this discussion, the stronger the correctness of the chosen line is ensured, the less the probability of error since in the course of a broad discussion each issue is considered from all different angles. In parallel, during this discussion, the theoretical level of the party activity rises, growing in the course of the political elaboration of argumentation and counter-argumentation.

Thus, a broad internal discussion on various issues is a prerequisite for the successful work of the party. This is the essence of the democracy of a new type of party.

However, this does not mean that every issue must necessarily be brought up for discussion by the party masses: with such an absurd approach, the very functioning of the party is paralyzed with more superfluous debate. Only the most basic, most important questions of theory and practice should be brought up to the public. In addition, when a situation requires urgent operational action or a party organization operates in an emergency (for example, when working underground or during the civil war), there is no mass discussion, and “publicity” of speech is also out of the question.

It is clear that the discussion of the party line or party events is impossible without criticism and self-criticism. With these tools it is possible to reveal mistakes for the sake of preventing their repetition in the future. But what is the nature of this criticism and self-criticism, what are their boundaries and how much freedom of criticism is permissible?

There is only one rule here: criticism should contribute to the ideological, political, cultural and organizational strengthening of the party. This is precisely what the criticism of the mistakes or deviations from Leninism is aimed at.

But if, under the slogan of “freedom of criticism”, criticism does not strengthen the party and instead weakens it, if it leads to the destruction of party structures, to the strengthening of petty-bourgeois and bourgeois tendencies in the ideology, to the party’s separation from the working class, and even more so to rejection ( even veiled by a “revolutionary” phrase) of revolutionary goals – such criticism should rightfully be perceived as a bourgeois instrument for destroying the revolutionary party of the proletariat.

Democracy in the new type of party ends where the implementation of decisions adopted by the majority begin. At this stage, as already indicated above, the party demands from its members the unquestioning execution of the decisions and resolutions adopted.

Thus, party democracy provides (with the exception of those cases specified above) for a broad discussion with the involvement of as many activists as possible speaking on the most important and significant issues. But when a decision is made by the majority, the task of all party members, even the dissenting minority, becomes the implementation of these decisions.

But this does not exhaust the essence of the democracy of a revolutionary party. Together with the strict requirements set on party activists, leadership itself is by no means a “caste of the elected” isolated from the rank-and-file members, above whom there is no rule.

On the contrary, the leading core of the Party grows out of the Party masses itself, which nominates, through the institution of the universal election of Party bodies, the most active, class-conscious, experienced and theoretically trained people. These cadres, as part of their management activities, are obliged to report to the lower bodies on the work done, on certain decisions, successes and failures, using the same tools of criticism and self-criticism. They are obliged in the same way to obey the decisions of the majority, which, based on the results of their work may require the removal of certain guilty persons from their posts.

This is the essence of democratic centralism.

Ideological unity

The unity of the ideological and political line is one of the most important characteristics of the Leninist revolutionary party.

The old social democratic parties and organizations had expressed the interests of several classes – workers, the petty and middle bourgeoisie. In this regard, there were various factions within them – right, left, centrists –between which was an exhausting struggle. This is actually quite natural. Under such a system, the right expressed the interests of the petty and middle bourgeoisie, the left expressed the interests of the proletariat, the poorest peasantry, and the intelligentsia leaning towards the working class.

The function of the centrists, vacillating between these two factions, was to subordinate the left faction to bourgeois and petty-bourgeois interests through all sorts of tricks, to actively hinder the development of the revolutionary process under the auspices “compromise”.

That is why the Bolsheviks advocated a split from the old Social Democracy, i.e. for secession of the proletarian faction from this multiclass organization, its separation into an independent communist party.

Due to its singular class orientation, the revolutionary party of the proletariat cannot be divided into factions. The presence of factions – separate groups that distinguish themselves from the mass of the party – signifies the transition of these groups from the positions of the proletariat to bourgeois or petty-bourgeois positions. It also means the desire of these groups to dissolve the proletarian ideology through the introduction of bourgeois and petty-bourgeois theses and positions into it. Splits in this class-structured situation cannot be interpreted in any other way.

Truth – proletarian ideology – is always unitary. The person who does not adhere to the truth follows the path of delusion, there is no third way. This means that the denial of proletarian ideology in total completeness and concreteness is adherence (even on some specific issues) to bourgeois ideology.

To allow the existence of such groups that violate ideological unity is to move towards the destruction of a single proletarian ideology. On the practical plane, factionalism manifests itself as sabotage of party decisions, in constant braking and stumbling, in the transformation of party work into a talking shop – creating conditions for the inevitable defeat of the revolutionary party.

The existence of various party “centers” which is characteristic of the Social Democratic parties is inconceivable for the party of the proletariat. Raunchy bourgeois pluralism and liberalism in this case contributes to the disorientation of the working class, and hence weakening its vanguard.

During the era of the “Bolshevization” of the communist parties, the course to strengthen the ideological party unity, to cleanse the communist parties of all sorts of reformists, centrists, defenders of abstract “democracy”, social-chauvinists and similar anti-proletarian elements, was also pursued by the Comintern. This explained the Bolshevik understanding of freedom, equality and democracy, the denial of which the communists were already accused.

“What is our stipulation for recognizing “freedom and equality”, the freedom and equality of members of the Communist International?

It is that no opportunists and “Centrists”, such as the well-known representatives of the Right wing of the Swiss and Italian socialist parties, shall be able to become members. No matter how these opportunists and “Centrists” may claim that they recognize the dictatorship of the proletariat, they actually remain advocates and defenders of the prejudices, weaknesses and vacillations of the petty-bourgeois democrats.

You must first break with those prejudices, weaknesses and vacillations, with those who preach, defend and give practical expression to those views and qualities. Then, and only on this condition, can you be “free” to join the Communist International; only then can the genuine Communist, a Communist in deed and not merely in word, be the “equal” of any other Communist, of any other member of the Communist International.

Comrade Nobs, you are “free” to defend the views you hold. But we, too, are “free” to declare that these views are petty-bourgeois prejudices, which are injurious to the proletarian cause and of use to capitalism; we, too, are “free” to refuse to join in an alliance or league with people who defend those views or a policy that corresponds to them. We have already condemned that policy and those views on behalf of the Second Congress of the Communist International as a whole. We have already said that we absolutely demand a rupture with the opportunists as a first and preliminary step.

Do not talk of freedom and equality in general, Comrade Nobs and Comrade Serrati! Talk of freedom not to carry out the decisions of the Communist International on the absolute duty of breaking with the opportunists and the “Centrists” (who cannot but undermine, cannot but sabotage the dictatorship of the proletariat). Talk of the equality of the opportunists and “Centrists” with the Communists. Such freedom and such equality cannot be recognized by us for the Communist International; as for any other kind of freedom and equality-you may enjoy them to your heart’s content!” (Lenin, “On the Struggle in the Italian Socialist Party”)

The revolutionary party is unable to fulfill its historical mission being split within itself. Effective actions by a revolutionary party are impossible without ideological unity.

Composition

The party of the working class is incapable of including the majority of the proletariat under capitalism. It is foolish to assume that under capitalism the entire class is able to rise in its consciousness and activity to the level of the vanguard.

Under capitalism, the party of the working class unites an overwhelming minority within the proletariat, i.e. the most advanced, most class-conscious and active members of the working class. Only such a policy meets those tasks of changing society towards which Leninists set themselves.

“True enough, in the era of capitalism, when the masses of the workers are subjected to constant exploitation and cannot develop their human capacities, the most characteristic feature of working-class political parties is that they can involve only a minority of their class. A political party can comprise only a minority of a class, in the same way as the really class-conscious workers in any capitalist society constitute only a minority of all workers. We are therefore obliged to recognize that it is only this class-conscious minority that can direct and lead the broad masses of the workers.” (Lenin, Speech On The Role Of The Communist Party, 1920)

During the Second Congress of the RSDLP, the Mensheviks defended the position of the “open door party”, upon which literally anyone can enter – from the schoolboy and intellectual suffering for the people to the small shopkeeper angered with the social order.

The Mensheviks strove to establish a typical Western-styled Social Democratic Party; a clumsy organization consisting of many loose groupings, the main task of which is to participate in a bourgeois-democratic performance.

Naturally, such a party is not capable of any truly revolutionary struggle: the motley class composition does not provide for monolithic unity or discipline, and the organizational structure does not know flexibility or mobility.

The Bolshevik faction, headed by Lenin, resolutely opposed such undertakings at all stages of the revolutionary process, emphasizing the need to combat the aspirations of bourgeois and petty-bourgeois democrats to dissolve the party of the proletariat in the proletariat itself, or in the abstract mass of the “people”:

“…fundamental error in the resolution is the slogan for “the creation of comprehensive democratic organizations and their amalgamation in an all-Russian organization”. The frivolity of the Social-Democrats who advance such a slogan is simply staggering. What does creating comprehensive democratic organizations mean?

It can mean one of two things: either the socialists’ organization (the R.S.D.L.P.) being submerged in the democrats’ organization (and the new-Iskrists cannot do that deliberately, for it would be sheer betrayal of the proletariat) — or a temporary alliance between the Social-Democrats and certain sections of the bourgeois democrats.

<…>

“Economists” (opportunist group in the Russian Social Democratic movement – PS) erred by confusing party with class. Reviving old mistakes, the Iskrists are now confusing the sum of democratic parties or organizations with an organization of the people. That is empty, false, and harmful phrase-mongering. It is empty because it has no specific meaning whatever, owing to the absence of any reference to definite democratic parties or trends. It is false because in a capitalist society even the proletariat, the most advanced class, is not in a position to create a party embracing the entire class — and as for the whole people creating such a party, that is entirely out of the question. It is harmful because it clutters up the mind with bombastic words and does nothing to further the real work of explaining the actual significance of actual democratic parties, their class basis, the degree of their closeness to the proletariat, etc. The present, the period of a democratic revolution, bourgeois in its social and economic content, is a time when bourgeois democrats, all Constitutional-Democrats, etc., right down to the Socialist-Revolutionaries, are revealing a particular inclination to advocate “comprehensive democratic organizations” and in general to encourage, directly or indirectly, overtly or covertly, non-partisanship, i.e., an absence of any strict division between the democrats. Class-conscious representatives of the proletariat must fight this tendency resolutely and ruthlessly, for it is profoundly bourgeois in essence. We must bring exact party distinctions into the fore ground, expose all confusion, show up the falsity of phrases about allegedly united, broad, solid democratism, phrases our liberal newspapers are teeming with.” (Lenin, The Latest in Iskra Tactics, or Mock Elections as a New Incentive to an Uprising, 1905)

Lenin firmly defended the path of creating an organization of professional revolutionaries who would stand exclusively on the class positions of the proletariat, strengthened by the expenditure of the proletariat, defending the interests of the proletariat. Therefore, Lenin made such demands on a party member which blocked access to the party from petty-bourgeois and intellectual elements, those dreamers, fantasizers and lovers of “freedom” and “equality” in their bourgeois understanding.

Let us repeat once more: the party is the vanguard of a class, including only the most conscious and ideological representatives of this class. At the same time, to confuse the class and the vanguard means destroying the vanguard itself, dissolving it in the general mass of the working class, which, under capitalism, is thoroughly permeated with a bourgeois and petty-bourgeois worldview. In other words, it means subordinating the party of the proletariat to bourgeois ideology under the guise of representing the working class.

Does this mean that Leninism calls for the creation, under the guise of a revolutionary party, of a small sect of “elected leaders”, isolated from the rest of the masses?

Of course not.

In his “What Is To Be Done?”, Lenin clearly indicates that the organization of revolutionaries must be connected with the mass of the workers, they must organize it and introduce revolutionary consciousness into it. However, at the same time, the organization of revolutionaries and the workers’ organization should not be confused.

“… The Economists are forever lapsing from Social-Democracy into trade-unionism. The political struggle of Social-Democracy is far more extensive and complex than the economic struggle of the workers against the employers and the government. Similarly, (indeed for that reason), the organization of the revolutionary Social-Democratic Party must inevitably be of a kind different from the organization of the workers designed for this struggle. The workers’ organization must in the first place be a trade union organization; secondly, it must be as broad as possible; and thirdly, it must be as public as conditions will allow (here, and further on, of course, I refer only to absolutist Russia). On the other hand, the organization of the revolutionaries must consist first and foremost of people who make revolutionary activity their profession (for which reason I speak of the organization of revolutionaries, meaning revolutionary Social-Democrats). In view of this common characteristic of the members of such an organization, all distinctions as between workers and intellectuals, not to speak of distinctions of trade and profession, in both categories, must be effaced. Such an organisation must perforce not be very extensive and must be as secret as possible.

<…>

The workers’ organizations for the economic struggle should be trade union organizations. Every Social-Democratic worker should as far as possible assist and actively work in these organizations. But, while this is true, it is certainly not in our interest to demand that only Social-Democrats should be eligible for membership in the “trade” unions, since that would only narrow the scope of our influence upon the masses. Let every worker who understands the need to unite for the struggle against the employers and the government join the trade unions. The very aim of the trade unions would be impossible of achievement, if they did not unite all who have attained at least this elementary degree of understanding, if they were not very broad organizations. The broader these organizations, the broader will be our influence over them — an influence due, not only to the “spontaneous” development of the economic struggle, but to the direct and conscious effort of the socialist trade union members to influence their comrades. ” (Lenin, What Is To Be Done?)

Thus, while making strict demands on the party of the proletarian vanguard, Lenin makes completely different demands on the mass workers’ organizations, which act more efficiently the more they contribute to the spread of revolutionary agitation, the more they directly embrace the workers.

The relationship between these workers (or mass) organizations of non-party people and the revolutionary party of the proletariat is carried out through the activities of the most advanced workers (party members) within them, who, by creating factions and groups, through agitation and example, step by step raise the general consciousness of the working class, strengthen their authority and the influence of the party itself, creating a personnel reserve of the party active members.

This is precisely the plan of the party’s work with the masses, proposed by Lenin and subsequently developed by Stalin, Dimitrov, Gottwald, Bierut and other leaders of the international communist movement, under whose leadership the revolutionary parties were able to rise with the masses of the respective countries to organize them and lead them to achieving socialism.

Contrary to the organizational principles of Leninism, revisionists from different countries and eras talk about the need to create, without fail, a mass revolutionary party, including any striker or tippler who’s dissatisfied with life. At the very least, they are talking about the confusion of the class and its vanguard, the confusion of the “organization of the workers” and the “organization of the revolutionaries”; the exposure of those principles to which Lenin devoted a whole subsection of “What Is To Be Done?”.

It is quite natural that, for the sake of quantity, such leaders forget about the quality of the party members, as a result of which, first the ideological and then the organizational unity of the party apparatus is inevitably violated.

The logical ending is the fatal collapse of the party organization, the establishment of all kinds of revisionists in leading positions and its transformation into a loose and powerless analogue of European social democracy under the red flag.

Flexibility

Unlike bourgeois or petty-bourgeois parties and organizations, which limit their work to any one direction, the Leninist party of the new type does not set itself any obstacles in methods of activity. Already in 1902, within the proposed framework of the plan for party building, Lenin demanded the creation of such an organization that;

“…will ensure the flexibility required of a militant Social-Democratic organization, viz., the ability to adapt itself immediately to the most diverse and rapidly changing conditions of struggle, the ability, “on the one hand, to avoid an open battle against an overwhelming enemy, when the enemy has concentrated all his forces at one spot and yet, on the other, to take advantage of his unwieldiness and to attack him when and where he least expects it”. It would be a grievous error indeed to build the Party organization in anticipation only of outbreaks and street fighting, or only upon the “forward march of the drab everyday struggle”. We must always conduct our everyday work and always be prepared for every situation, because very frequently it is almost impossible to foresee when a period of outbreak will give way to a period of calm.” (Lenin, What Is To Be Done?)

The ability to rebuild ranks with lightning speed, change “weapons” depending on the current situation, without abandoning the ideological principles set forth and maintaining monolithic unity is Lenin’s understanding of the flexibility of a party of the new type.

Such a party does not recognize organizational fetishism, when always and everywhere, under any conditions, an emphasis is placed on the once and for all established forms of functioning. Forms of an organization must obey revolutionary expediency, and not some eternal rules. Proceeding from this, the party is modifying its organizational forms, while remaining a party of a new type.

This point is extremely important.

Neither the rebuilding on a military scale, relevant in the era of the civil war, nor the adaptation to the bourgeois-democratic forms of struggle in the era of revolutionary recession, nor the combination of legal and illegal methods of action, whose urgency is obvious in the rise of a revolutionary tide, does not lead to the loss of the Bolshevik character by the party.

The flexibility of forms and methods excludes the ossification of the party organization or one-sided deviation towards any one form. That is, even in the conditions of “developed parliamentarism”, the Leninist party does not turn into a bourgeois-democratic party of the parliamentary type. Even in conditions of active armed struggle, the Leninist party does not turn into a narrow group of underground conspirators or a purely military organization.

Despite the change in forms, the party retains its revolutionary content and the ability to instantly rebuild according to the requirements of the current moment.

Revisionists are incapable of such flexibility and rapid restructuring due to the lack of centralism, discipline and ideological unity on the basis of Marxism-Leninism. As history shows, the slightest departure from “established” forms of action immediately causes splits in revisionist groups, lengthy discussions and outright sabotage, paralyzing all work.

Clumsiness, practical constraint, inability to provide adequate answers to the challenges of real-life and, ultimately, ideological death is the natural result of the rejection of Leninism.

Activity

The question of the activity of party members is probably one of the most important aspects of the character of the party of the new type, from which, in fact, Bolshevism began.

Let us recall that in the early years of the 20th century, the Social Democratic Party did not actually exist yet. The Russian socialists had just overcome the club, “handicraft” stage in the development of the revolutionary movement, which no longer met the needs of development, and now they were at a crossroads – where to go next?

In August 1903, the Second Congress of the RSDLP was held, at which Lenin entered into a sharp polemic with the Mensheviks over the question of who can be considered party members. The Mensheviks advocated the construction of a broad leftist party typical of the West, uniting in its ranks all sympathizers of Social Democracy. In their opinion, anyone who agrees with the program and provides material support can be considered a party member. Actually, such members are not required to do anything special: regularly throw off monetary contributions, vote for whom they indicate, and from time to time take part in some party gatherings as extras.

This is how the Social Democratic parties of the past were built, and they remain so to this day. Amorphous, apathetic, inert actors in the theatre of bourgeois democracy. Today, a similar party scheme has already been adopted in the overwhelming majority of the self-acclaimed “communist parties” that have turned into a left-wing version of spineless social democracy.

Lenin categorically refused to accept this position, stating that in addition to sympathy and material assistance, a party member must personally work in one of the party organizations.

That is, the title of a member of a new type of party imposes certain obligations. A communist cannot simply “be a member of an organization”, formally serving a number. Each party member is required to actively work to strengthen, expand and increase the effectiveness of party actions. The passivity and inertia of the cadres is the death of the revolutionary party, for having such cadres, the party is unable to solve the set tasks.

On the contrary, on any front, the party member must show initiative and activity, raising their authority by their energetic actions and strengthening the influence of the party among the masses. Indeed, a healthy party atmosphere itself does not require the masses to be passively “present,” to “approve”, or “condemn” along some line, but rather actively participate in party life, in discussing certain issues, and in the struggle against shortcomings and mistakes.

The party is the vanguard, the vanguard of the class, and it cannot, without losing this title, drag behind the spontaneous labor movement, lose its head in front of the fact of indifference, inertia and cowardice on the part of a significant part of the proletariat. These elements are brought up by capitalism in the spirit of servility and obedience, to be a servant of the momentary demands of the masses, ready to betray class interests for small handouts of the bourgeoisie.

Without the activity, audacity and decisiveness of the party cadres themselves, the party is not capable of dissolving the servile worldview impressed upon the working class, of raising its consciousness to the level of awareness of class interests, nor, even more so, leading and directing the proletariat along the revolutionary path.

Meanwhile, moving in the tail of the spontaneous economic or political discontent of the working class is a particular feature of the inert Social Democrats and revisionists who restrain the buoyant energy of the masses by directing it into a channel that is safe for the bourgeoisie.

The task of this new type of the party is to give this spontaneous discontent a conscious and organized character, to instill in people a hatred of their economic system, to show essential guidelines for the mass movement and lead it to the liquidation of capitalism.